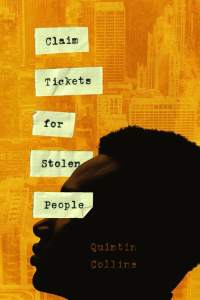

Quintin Collins’ second collection of poems, Claim Tickets for Stolen People, was selected by Marcus Jackson as winner of The Journal’s 2020 Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize.

Quintin Collins’ second collection of poems, Claim Tickets for Stolen People, was selected by Marcus Jackson as winner of The Journal’s 2020 Charles B. Wheeler Poetry Prize.

Ilan Mochari: In your notes you mentioned the inciting impulse for Claim Tickets for Stolen People was the poem “The Moon is Trans” by Joshua Jennifer Espinosa. Can you elaborate on what it was about “The Moon is Trans” that set your muse in motion?

Quintin Collins: After reading “The Moon is Trans,” I considered what space the poem occupied besides being a poem on the page. It inspired me with its claim to a public object for trans people and culture. Appropriation and the colonial past of the U.S. haunt nearly every moment, and this poem showed me a vehicle to hit back at these structures. Essentially, “The Moon is Trans” encouraged me to say, “Hey, I want to do something like this for Blackness and for an entire book.” From there, I made a list of places, things, sentiments, and more to claim and reclaim for Blackness, as well as drew inspiration from examples that already took on this work, such as the Afrofuturism movement. Then, all I had left was the hardest part: writing the poems and doing so in the language of my people.

IM: I savored your attention to sensory details—especially sound. In “Downtown Chicago, a Decadence Uncommon,” the reader hears clinking change, clicked tickets, and a “gull-sung serenade.” In “Petrichor,” the rain “raps the air unit: hi-hat or timpani,” until the drops “tumble into a drum roll.” There are also numerous references to recording artists: Aretha Franklin, Barry White, Jay-Z, Diddy, Little Richard, Prince, Jimi Hendrix, Parliament, and Janelle Monae. Not to mention A Tribe Called Quest in your Notes. How did sound become such an essential part of your artistic sensibility—and, by extension, your poetry? And how did your ear for sound—and talent for describing it—evolve in the course of drafting and revising these poems?

QC: My fascination with poetry grew from a love of hip-hop and my parents watching episodes of Def Poetry Jam. Then I had access to YouTube and videos of slam poets. So sound has always been an integral part of my work. As I learned more, I gained a greater understanding of how to use sound intentionally from phonemes to syntax and everything else. For this book, music and references to it felt essential because it’s a key part of my culture. It’s an intergenerational thread, as well as one of the ways we most publicly produce and engage in art. The music had to hit when it needed to hit and disappear when it needed to disappear. The music needed to drive you through the poems but sometimes slam on the breaks so you can contemplate the silence. From a personal, non-craft perspective, I just love the mouthfeel of saying certain strings of words.

IM: As I was reading Claim Tickets for Stolen People I happened upon the description of a course to be taught by Major Jackson. One of the lines in the description—“The poem emerges as a testament of our existence”—struck me as especially apt for Claim Tickets, since throughout the book I felt like I was swimming in the waters of an “our” rather than those of a “your” or a “my.” How did you go about selecting and sequencing the poems in Claim Tickets to create such a testament of “our”? I could point to the commingling of intensely personal subjects (“Sonograms,” elegies, homages to fathers, uncles, wives, daughters, best friends) with history and current events (“Generation Snowflake,” “Black History Year,” five poems alluding to Barack Obama, references to Charlottesville, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Rekia Boyd, and Trayvon Martin).

QC: My debut, The Dandelion Speaks of Survival, is personal although it contains a lot of synthesis of shared experiences. I started on Claim Tickets as I was sending out Dandelion (and revising after a lot of rejections). Based on my initial inspiration, the goal of the book, and trying to do something different for book two, Claim Tickets had to be communal. The poems that seem personal through their subject matter and/or pronoun usage still get at a shared sentiment; I just put the “voice” for that sentiment in one mouth for the sake of certain poems. Claim Tickets is supposed to feel like chaos in that it’s not completely grounded in a linear narrative, and in the midst of that, you have a chronological story of coming parenthood. I mostly tried to “attach” poems to each step along the journey. However, the parenthood poems were unexpected. I told myself I wouldn’t write them this soon after joining the club, and then it happened. How could I not when all that appears in these poems actually surrounded the real-life journey?

IM: At what point in the creative process did you realize the title Claim Tickets for Stolen People could encapsulate what you wanted the book to encapsulate? I was curious in part because the book does not have a poem by that title, but it does have one called “At the Baggage Claim, I Collect Myself” and another called “The Stolen People Do Decree.”

QC: I originally took a page out of Morgan Parker’s Magical Negro and numbered various poems that spoke to specific totems for the task. However, the approach began to feel more like a gimmick than useful, especially considering those numbers came with titles that felt compelling on their own. I thought about having a title poem for this book, but then I remembered the goal was to fight a sense of singularity. Sure, no matter what, one poem can turn out to be the poem for a book. However, I wanted to take no part in directing that decision for this book by avoiding a clear title poem. Otherwise, I had a few threads that came together. I also have to thank my good friend Daniel B. Summerhill, who provided a lot of guidance on the arrangement.

IM: From my first four questions anyone unfamiliar with the book might be surprised to learn Claim Tickets for Stolen People includes a number of what might be called nature poems, in which the poem depicts the behaviors of squirrels, spiders, bees, and starlings, and infuses them with allegory. Though you mentioned in your notes that “The Moon is Trans” was the book’s inciting impulse, I’m wondering if, as well, you find much of your muse in nature and biology—in gull-sung serenades, as it were.

QC: The funny thing is I don’t run to nature right away. For this book, I believe the inspiration was easy because of its collective sense of connection to, through, and around the world. Bees are dying, and not enough people care. Black people are dying, and not enough people care. I have middling feelings about a cosmic will binding all things in the universe depending on the day, but it’s no coincidence that the people who won’t take global warming seriously are the same people who will pass legislation that further facilities police brutality, discrimination against trans individuals, and so many more harmful policies. I can think of these poems as being akin to unseasonably warm days in winter or the massive and disastrous storms of all kinds in recent years. All struggles are in conversation, and they’re all choosing a less quiet approach to listing the demands and setting the deadline for change. Claim Tickets seeks to acknowledge that with the poems you highlighted. But it’s not all bad. We still have glorious summer days when the temps are just right and the music of joy echoes up and down every block. The poems want to celebrate that, too.