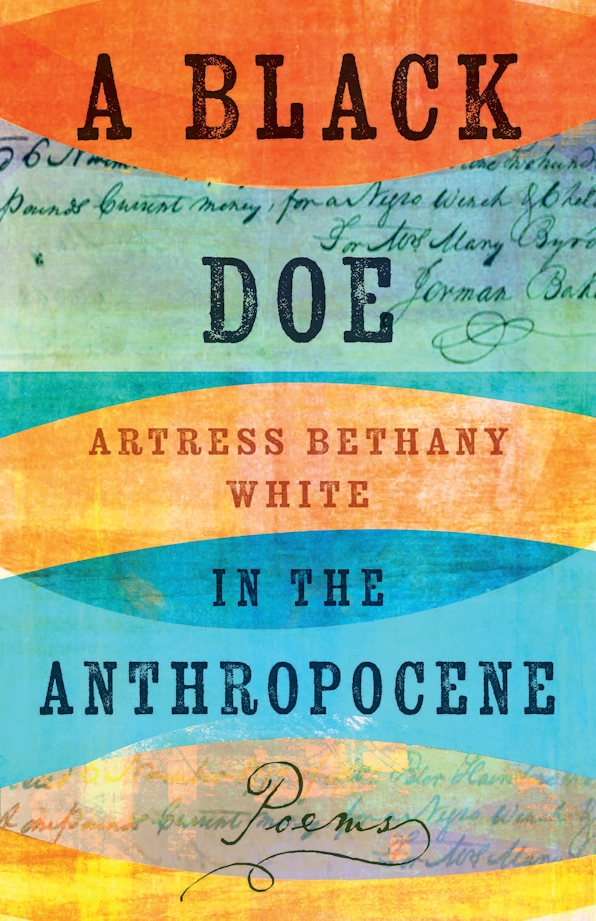

A Black Doe in the Anthropocene

By Artress Bethany White

Univesity Press of Kentucky

2025, 104 pages,

$19.95

In the title poem of her remarkable new poetry collection, A Black Doe in the Anthropocene, Artress Bethany White recounts a tense encounter with an armed landowner as she is exploring the pine woods around the North Carolina plantation site where her ancestors had once been enslaved. The incident took place in the weeks following mass shootings in a mall in Buffalo and at a school in Uvalde, and White describes the instant in which a thoughtful pilgrimage to trace her ancestry becomes a dangerous standoff charged with deadly force, reverberating with racial overtones that echo across centuries of subjugation and struggle:

What is it about camouflage and tactical

gear that recalls white sheets and a

deadly sneer?

The poem then circles around from the consequences of contemporary spasms of racial violence to the epic sweep of the Middle Passage and the slave trade, and the renewed effort to erase that cruel history from our textbooks and our consciousness. In doing so, it underscores the poet’s risky task:

…I would become

a black doe in the Anthropocene

fighting to see without being seen.

White is a scholar, a poet, and a keen social observer, and she skillfully brings all three of these vocations to bear in constructing this collection, which is part family history, part travelogue, and part historical narrative. She has a remarkable capacity to embrace the complex and painful ambiguities of her investigations. In particular, she looks long and hard at the most harrowing aspects of her own ancestry, what Barbara McCaskill describes in her introduction to the book as “the normalized rape and molestation of Black teen girls,” and the realization that a number of her forebears were Scottish plantation owners who forcibly impregnated the young women they held as chattel. In “A Bondage Nocturne” she intones:

A chill pricks my heart when I read the name

of the third enslaved girl to bear a child at age fifteen,

conception like clockwork proclaimed.

and:

While her eyes stammer back neophyte / [he] whispers temptress. /

Talks

abed narration. / A girl fears a feral man / with ownership rites / a

tug-of-war

under yellow Scottish overbite.

But she refuses to allow herself or her maternal ancestors to be defined by victimhood. In “What I Will and Will Not Take from a Planter Ancestor” she declares:

Hairston.

I will have the name because it came

by way of blood and stripe…

I will leave behind the self-righteous greed

She is even able to inject an ironic humor into her circumstance. In “Severed: A Statement on the Ludicrous Nature of African Repatriation” she considers the results of an ancestral DNA test which would require her body to be apportioned out for homeland repatriation, with twenty-four percent of her delivered to Mali, four percent to Norway, forty percent to Angola, twenty-eight percent to the British Isles, and so forth.

A Black Doe in the Anthropocene is meticulously researched, and White deploys her source material throughout the book to great effect. Some of the pieces in the book are found poems, culled from archival receipts and documents, such as “Runaway Slave Affidavit Dated March 1831.” These forefront the slaveowners’ callous indifference in their own words. The frontispiece is a facsimile of a scrap of parchment inscribed: “Rec’d of November 1777 of Mr. Peter Hairston two hundred & one pounds current money for a Negro Wench and child for Mrs. Mary Byrd.” White reflects on this transaction in a subsequent poem:

I want to divine her name and that of her babe,

know much more than this receipt entails.

It is not enough that the sweat of the planter seller

is mixing with the sweat of my fingertips.

She counters these bald receipts, where all traces of Black humanity are erased, with snippets of storied evidence passed down generationally, as in “Oral Slave Narrative” and in the brilliant poem “Pancakes Keep Coming to Mind: A Sestina Commemorating the Demise of Aunt Jemima on the Pancake Box” where she deconstructs the stereotypic kerchiefed trope of Aunt Jemima and uncovers the authentic Mima, which she learned was her great-great-great grandmother’s name:

What I seek is what I speak, not handed a script of nostalgic

longing.

Jemima wrenched from shelves, but a litany in my brain still playing

out.

Ain’t nothing but a jonesing to tweak culinary history so my village

knows my branches are thick, swaying and swinging with longing

and breath,

rolling descendancy off my tongue, blessing consumption out.

White makes frequent use of traditional poetic forms, including the villanelle, the nocturne, and the aubade, but she subverts their conventional European function. As McCaskill points out, these forms were intended as love poems, but White uses them as vehicles for more gut-wrenching themes: exploitation, survival, a longing for justice. In “George’s Dilemma, Anno Domini 1777” the repeating lines of the villanelle illustrate an enslaved man’s struggle to decide whether to obey his master’s call to arms as the War of Independence winds down, or to take sides with the British, and the tenuous possibility of earning freedom. In “Plantation Aubade: Freedom as Lover” the convention of a lover leaving at dawn is replaced by a cruelly elusive ideal:

the soul petals at dawn

reaches back to what it once knew

before being penned to another’s dream;

house and field bearing your blood but never your name.

The book unfolds in three parts. The first, “Original Sin,” is broadly grounded in the experience and consequences of slavery in America. In the second, “Back to Africa,” White journeys to Ghana and visits Elmina, the coastal fort where the newly enslaved were processed to embark on the Middle Passage, where she describes ambiguous feelings of homecoming:

My return to Ghana a corrective

to being ripped from its womb

by a system built on the ovaries

and backs of stolen African queens…

I walk into the holding cells and palm rough walls,

assailed by a return awash in pained sobs.

She includes a fascinating sequence of poems that chronicle a little-known historical chapter: a program of Black American repatriation to Africa under the auspices of the American Colonization Society in the nineteenth century, devised to resolve the “problem” of the growing population of free Blacks on American soil, often underwritten by former slaveowners. The program was a fiasco; many died of cholera and harsh living conditions on arrival in Africa, and some returned to the States while others struggled on in makeshift communities that remained culturally apart from the indigenous majority. This section, with its sweeping dislocations back and forth across the Atlantic, sheds a new perspective on the chaos and the tragedy of the Middle Passage.

The final section (there is a surprisingly humorous afterward) is titled “Home Again,” and White returns to set her focus to America, in the post-Civil War Reconstruction era, where the air is rife with “distrust between broken masters and broke slaves,” and soon the landscape is dotted with “stark Black voter intimidation, / bodies in trees and filled with holes.” This is not a welcoming homecoming, and White extends the discomfort into the twenty-first century in the poem “A Meditation on the Toppling of the Confederate Statue Silent Sam,” with images of a blackface governor and tiki torch-brandishing Nazis marching through Charlottesville, and the threatening rumble of refrain that “the Old South will rise.” The final poem in the section is “Slivers,” a slender observation that humans are comprised of 99% identical DNA, yet that one percent of difference has been enough to provoke our long history of racial tension and violence. In coming home, White has not found resolution, rather a renewed resilience, embodied in her powerful line, “Every day can’t be rebellion, but will be resistance,” an intention that reverberates throughout this compelling and necessary book.

Robbie Gamble’s essays have appeared in Scoundrel Time, Pangyrus, Pithead Chapel, Under the Gum Tree and Tahoma Literary Review. He was a 2019 Peter Taylor Fellow at the Kenyon Summer Writers Workshop. He worked many years as a nurse practitioner caring for homeless people in Boston, and now divides his time between Massachusetts and Vermont.