“Where we live is at the center of how we speak.”

⸺Terry Tempest Williams

After ten years away the old ground looked about the same. Exposed bedrock of red sandstone and limestone, juniper-piñon woodlands. Oak brush, pads of prickly pear, claret cup and hedgehog cactus with their explosive yellow blossoms. The balletic cholla, the banana yucca. Flax was common in the spring. Mesa daisies, penstemons and Indian paintbrush grew along our paths. Blackfoot, snakeweed and bahia. Heath asters grew along the arroyos. In the foothills, on the southeastern edge of the Sangre de Christo mountains, hundreds of years of topsoil erosion has created a kind of stone floor a few hundred feet behind our old roadhouse, itself made of native rock and built in the 1940s.

Throughout the post-war years of Northern New Mexico, it saw daylight as a tavern, a store, a gas station, a family homestead. Much later, it kept my wife, my father and extended family and friends warm and dry for twenty years. It resides across the road (now Interstate 25) from the villages of Bernal and Serafina and that wily old sentinel, Starvation Peak. It is located on the Santa Fe National Historic Trail and the pre-1937 Route 66. Fifteen miles south of Las Vegas. This was Billy the Kid country. Jicarilla Apache country. Las Vegas is still home to the building that housed the jail where William Bonney (Billy the Kid) was incarcerated after his capture and arrest by Pat Garrett.

(Filmmakers have long appreciated Las Vegas and environs for its historic echoes from Tom Mix through Easy Rider and No Country for Old Men. The popular TV series Longmire was filmed here as well.)

Starvation Peak (really, more a flat-topped butte than peak) was a 7,000-foot landmark on the historic trail. Just beneath it was Bernal Springs, a stopover for early travelers on their way to Santa Fe. Its name is derived from a legendary incident where a party of Indians, sometime after the Pueblo Revolt, chased 27 (or 36) Spanish colonists up to the top of the butte and either killed them outright or starved them out. Historians suggest the unfortunate could’ve been freighters due to their proximity to the trail. A memorial was placed at the top many years ago to commemorate the event.

The roadhouse is located about two hours from Albuquerque and the desert.

I came back for a visit and brought some of my old dog Ruby’s cremains with me to spread on the terrain she spent her first five years hunting, chasing, stalking and wandering across. She lived fourteen years. It’s not too far from my current home in the small city of Santa Fe. Maybe there was some unfinished emotional or sentimental business between the old roadhouse and myself. Echoes and memories not properly or coherently dispersed. Basically, we aged out of it. It became too long a journey to my work in Santa Fe. I had lost my enthusiasm (and some of the musculature) required for seasonal upkeep on the place. My wife Annie, though, she was crushed at having to leave her home of so many years (she was the one who discovered it while visiting friends), took the distance and separation more in stride. She spent more time at home than I did⸺ being an artist, she discovered painting wildlife on gourds was a fine way to spend the day and make a few bucks, along with taking care of my father, walking the dogs, preparing meals, planting gardens and trees and praying for rain⸺ when it came to that ground, she was in the process of becoming indigenous.

At forty years old, being a writer and a freshly transplanted New Mexican, I gratefully rediscovered my language. I had been a short story writer and poet most of my life with several outlaw books published and this land, this open space, began coaxing to the surface ideas and feelings that had been evidently languishing in my exhausted imagination. I had published poetry anthologies, edited an arts journal. Practiced journalism. I guess I made up the job as I went along but the work that needed to be done on that house was nowhere to be found in the conjured job description.

It was a good day and warm for late January. The layers of sandstone reflected the sun’s heat. Sometimes a windy place, today it was as calm as an empty gesture. Its wildness that day was accentuated by nuisance-engorged coyotes free to run across my field of dreams⸺ a few tracks and some fresh scat near the arroyo.

One year, during a drought, I saw a large black bear behind the house and for three or four rainy years we had seen and heard more than our fair share of Western Diamondback rattlers.Diamondbacks (Crotalus atrox) aren’t generally found higher than 6,500 feet. So, at our house they’d reached their northernmost range and altitude. Their presence around us was both a curse and a blessing. We encountered them mostly in the shade underneath junipers and near the arroyo and once we were all alerted to our collective presences, we safely detoured. Our neighbor shot one, a large one, about five feet long, around his house one day and displayed him proudly hanging from a rake. The rattler looked certainly formidable and better dead than my neighbor did alive. (They just want to be left alone as well. That’s why they employ an effective early warning system.) Most of the people bitten by rattlesnakes are young, male and drunk. Mercifully, none of the dogs were bitten but a couple of them weren’t as wary as the others. I promised my wife and myself I wouldn’t harm one unless it found its way into our half-acre fenced yard. After all, it was their ground and they’re extremely effective predators in an environment filled with mice, rats and gophers. We also had bull snakes and garter snakes (and there is some controversy as to whether or not bull snakes or gopher snakes, are a threat to rattlers.) Their diets are basically the same. One summer a shy pair of non-venomous Western coach whips emerged out from under a large rock near our raven feeder. They consumed rodents and were especially fond of the lizards.

I’ve never seen or recognized a rattlesnake track although they do leave easily definable trackways that are mostly straight and noticeable on sandy or bare ground and become serpentine when in a hurry, but that’s rare. I would imagine following a snake’s trail with anything beyond pure curiosity may take an Apache or a local curandera, someone with a more spirited relationship with the medicinal properties of all five senses.

Yes, for some of those years I wish it had been more about the rain and snow and less about the wind⸺ some years the wind spoke only in romance languages, some years the wind was a desert without borders, the sky’s vanquished whisper⸺ some years the land surrendered to winter’s empty grave of drought. I’m thinking of the last two lines of a poem by the Kiowa poet and novelist N. Scott Momaday, a beloved New Mexico resident, who passed on this very day at eighty-nine⸺ it is not a matter of time/but rain.1

But I think we gave as good as we got. One marriage, five lively dogs who grew into old age, died and were buried. It had been empty for years when we bought it and we eventually put on a new roof, double-paned windows, new stucco outside, new plaster over stone inside, replaced floors, closets, shelving. We brought in a new water main. Wood stove and propane heat. The structure had to be rewired from top to bottom. We landscaped the back with raised garden beds, planted drought-resistant trees and a stone patio. We recycled, composted and our primitive moisture catchment system included stock tanks, plastic trash barrels and rain gutters. We built on a mud room and a deck. One seized up lower back from years of lifting the spirits of a place, from twenty years of splitting cord wood. We bought it cheap and brought it back.

“But mostly I was poking around. Climbing higher to get a better look. Reading the plants and the rocks. And reading books. Nothing noble. I was having fun.”⸺Luis Alberto Urrea 2

Early on, we named it La Cantera, (Spanish for quarry), which is where the old casita stands. A trajectory of nine letters assembling themselves into a beautiful Spanish word that became our place, our home, our querencia, our light at the end of the day. It was built literally from the ground up. Stone and adobe were its skin, its marrow, its gravity and heft.

It’s now abandoned again, empty and for sale⸺ just speechless, pitiless spirits inhabit its space, addicted to the wind and rock, on this northern llano’s edge.

A typical clear January night was a solid black observatory of stars so deeply imbedded that they must’ve looked like how the Mayans saw the celestial heavens in a single jaguar’s skin or, how the Tlingit-Unangax artist Nicholas Galanin painted the night sky onto a deer hide, seen as part of a recent Santa Fe installation. The darkness was non-negotiable, resolute, no city lights, no shadows. When I walked out back I felt suspended in it, the forest beyond seemed like a haunted rumor.

In the mornings, sometimes red and orange-hued clouds, expanding with the mutable textures of sunrise, reminded me of a smoldering Mexican blanket rolled carelessly across the horizon. Soon darkness fades revealing a mesa here and there, meandering smoke from a village chimney, the Llano Estacado, (Staked Plains) in the distance; elongated Sombodoro Mesa rises a couple of miles to the southeast. Down the road near the village of Tecolote (owl), an unexcavated twelve-hundred-year-old pueblo is hidden like a crypt behind the walls of an arroyo.

one summer the rattlesnakes began singing at dusk

Occasionally, we’d unearth a small arrowhead or bird point behind the house. Flints and flakes.

We fed the ravens, scrub jays and hummingbirds. One day I was queried in silence and up close by a piñon jay about a few stray nuggets left in a nearby dog dish. In 2023, it was determined that this species of jay has lost eighty-five percent of its habitat over the last fifty years. Clearcutting of juniper-piñon woodlands for development, an increase in wildfires due to climate change, are two of the culprits contributing to their rapid decline. In our area, Scrub jays lived year-round and were common. Stellar’s jays were an occasional pleasant squawking surprise. Turkey vultures assembled in the skies over the blood and guts of some roadkill and were ubiquitous⸺ the poet Lew Welch called them unkillable wing-locked soarers. They’d float like lazy savants in monotonous cursives high above the house and highway but they were reassuring in some way, as if they were weaving the unraveling sky back together with invisible threads trailing behind, seemingly well aware that their jobs were, to keep the highway clean and bother no being.”3

One summer a plump homing pigeon landed exhausted and disoriented on the tin roof of our little mud room and stayed a couple of days, evidently recovering from being blown off course. We fed him some bird seed. He seemed tame. On the band around his foot was printed the phone number of his owner who used him for sport. He told us to just give him a little time and he’d fly off for home once he’d rested. The next day he started to coo or talk. The dogs ignored him. Sure enough, on the third day he took off and never looked back.

One day we watched in horror as a tarantula hawk, the garish spider wasp that feeds on tarantulas, snatch a clueless orb weaver out of its web, sting it and drag its paralyzed body several yards to its hole where it would proceed to lay eggs on the spider’s round belly. It left a meticulous track you could only see at ground level. This chimera, which didn’t make you feel totally safe on planet earth in its presence, is the official New Mexico State Insect. They also may be as cool as Miles Davis.

With the exception of the aforementioned gangster wasp, Ruby chased them all (rabbits, mice, gophers, songbirds, corvids) and unless one was sick or a nestling, to no avail. We adopted her from a gulag known as the animal shelter in Las Vegas. She was about eight months old, medium-sized with long black hair, a mixed-breed something or other, and she steadfastly remained, like most everything else that lived and breathed, visited, wandered, wove a web above or burrowed beneath that swatch of land, incurably feral⸺ we divined her to be part coyote, part earth goddess without portfolio⸺ the raw lawlessness of the ground suited her. After we had her put down, on the way out of the vet’s parking lot on a warm May day, my wife played the Stones’ “Ruby Tuesday” on her iPhone.

This evening night hit the ground running, there were star fields of questions no echo answered, just this solitude this exercise in virtues of consciousness. For you, Neruda, it was the white hot killers of angry Spain and the Chilean blood of deserts; for me, maybe it is this old stone house made of legends, the Rio Grande running broad and full, a jungle of a bosque, the low brow humor of coyote⸺ in the whisper of a shooting star parched from a million light year crawl across the universe. Or, do the answers come from “the rain that often struck your words/filling them with holes and birds.”?4 Some nights I am at a loss for the words when I should be soused with them or at least tracking them through the night, across the moon or up desert rivers to their source.

I used to experience a kind of meditative bohemian bliss sitting out behind the house on my days off surrounded by the red rock and a rotunda of blue sky pierced only by a contrail or two and the junipers waving like dry paint brushes in the unsubtle breeze. I strung small Tibetan prayer flags facing the sunrise between juniper branches near where I sat. After a rain, puddles would form in the horizontal, concave stones that resembled pre-Hispanic epoch metates, used for grinding grains, especially corn or wheat. Some days I could feel the weight of the earth’s troubles in the dry air, other days I was liberated by the rare moisture.

The late author Charles Bowden once wrote, “The West is an undeclared war.” Yes, on itself, on piñon jays, on watersheds and forests, wide open spaces, wildernesses, endangered species, immigrants, the borderlands, on this disturbed earth in general, but maybe not here, not now at this fraught moment, standing here with an old dog’s ashes in a small bag in my pocket and yes, the earth and its oceans are disturbed, there are too many of us on the planet, developers run amok⸺ the contemplation of such things sends many of us into paroxysms of anger, guilt or helplessness⸺ and just forming sentences out of these dysfunctions is enough to drive us into sanctuaries of disturbed silence.

But the day was sanctuary enough. Her ashes would remain invisible to borders. As would her tracks.

***

The wall at the southern border, about three hundred miles south of the old house, never could totally impede the traffic of immigrants crossing over from Mexico, Central and South America. They cross the Rio Grande, they cross the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts into an uncertain hell, they cross in all seasons. Some are mothers and fathers, children, some carry drugs. None of their tracks look the same⸺ once imprinted and abandoned on the desert pavement, they fall prey to the elements, they disappear into the fine dust as if they’d decided in silence, mid-journey, that the gods no longer looked with favor on their souls. But this trek is desperate and holy nonetheless. They risk being separated from their families, they risk arrest, robbery or dying of thirst. They risk leaving behind nothing but tracks.

The tracks speak history, have lives of their own. Just ask the typical javelina family, its migration trail obstructed by the wall; just ask the northern jaguar just now feeling its way into the wilds of southern Arizona from its habitat in the Sierra Madre.

I’ve never seen a northern jaguar (panther onca) in the flesh, across from me or crossing the border or anywhere else, but then, I’ve never witnessed the birth of the blues or border author Chuck Bowden’s feral ghost. But I believe in them both. Just as I believe in the hot dry ground that sings under its breath for rain; that fantasizes with all of its stoic forbearance: one day it’ll ride the storm out once again.

The ground still gathers itself at the horizon for the redundant miracles of twilight. The cooling, the operatic softening. Perhaps, for the jaguar’s silent tracks as well: south of the border but close, so close, slowed on its journey by drought, or human predation, the wall. Maybe a sordid combination of all three. I’ve been to parts of the wall where no road ends in a landscape that seems, to quote the late poet Jay Hopler, “empty for 1,000 years in both directions.” I’ve trekked through organ pipe cactus forests that take up as much space and distance in the sky as they do on earth.

The jaguar has marked its territory with myth.

The Mayans believed if you spread out the skin of the jaguar, you’d see a map of the celestial heavens.

In a perfect world, their range would include the American Southwest all the way down into Argentina as it did a thousand years ago. They’re considered endangered in Mexico and in the U.S. if and when they ever make it this far north. There are rumors rampant. Some legitimate sightings over the years. In northern Mexico, in the Sierra Madre Occidental, his home territory, the Northern Jaguar Reserve⸺ the wildest, most isolated place, where between 8 and 20 of them roam, mate, raise their young and survive⸺ is located about 125 miles south of the U.S./Mexico border and is a protected space. It is 56,000 remote acres of canyons, perennial streams, sheer cliffs, jagged mountains and forests. It is managed by the non-profit Northern Jaguar Project, headquartered in Tucson.

The Northern Jaguar Project also manages Viviendo con Felinos, which operates at the core of the Project’s mission statement and its brilliance is matched only by its fraught simplicity. Many jaguars, as well as the Reserve’s other feline inhabitants including pumas, lynxs and bobcats, were at the mercy of ranchers whose livestock were endangered by these predatory cats. Viviendo con Felinos has contacted many ranchers and reached an agreement beneficial to the humans as well as the felines. If they could get ranchers to hold off on gunning them down, Viviendo con Felinos would pay them for every large cat caught on one of the many cameras set up throughout the Reserve. Capturing still (or video) footage of a jaguar passing through their property produces the biggest reward for the rancher. Since 2007, they have worked with ranchers in this “buffer zone”, easing tensions and hostilities that have persisted for generations. According to the NJP website, “Participating ranchers sign contracts not to hunt, poison, bait, trap, or disturb wildlife, including the area’s four felines – bobcat, ocelot, mountain lion, and jaguar – and the deer and javelina they prey on. We place motion-triggered cameras on their properties, and they receive monetary awards for feline photographs.” In addition, “Every rancher has been challenged by unprecedented and prolonged drought. We assist with water infrastructure and restoration projects, expanding the network of gabions and other earthworks to slow stream flow, curb erosion, stabilize soils, and help re-vegetate habitat. For ranchers concerned with depredation, we provide site visits to discuss strategies to minimize human-wildlife conflict.”

In addition, if a never-before-seen jaguar is captured on a ranch’s camera, the rancher gets the opportunity to name the cat. So far, El Jefe, Valentina, Tito, Libélula, El Guapo, Angel, Don Julio and others have graced the arroyos and trails of Vivendo con Felinos

“Around the campfires of Mexico there is no animal talked about, nor more romanticized and glamorized, than el tigre. The chesty roar of a jaguar in the night causes men to edge toward the blaze and draw serapes tighter. It silences the yapping dogs and starts the tethered horses milling. In announcing its mere presence in the blackness of night, the jaguar puts the animate world on edge. For this very reason it is the most interesting and exciting of all the wild animals of Mexico.”

– A. Starker Leopold, Wildlife of Mexico

Jaguars once roamed as far north as the Grand Canyon. Several jaguars have been seen in Arizona and New Mexico since the mid-1990s.

Jaguars have blue eyes when they are born but when adult, their eyes glow like torches in the moonlight.

I’ve never seen a jaguar in the wild but I see them in my dreams and when they see me, their gaze pierces to the heart. These jaguars are smaller than their South American cousins.

They’re the only mountain lion that roars.

Their colorful skins can be seen on an Aztec codex from the 16th century.

In Mesoamerica, the jaguar is a powerful symbol of the underworld. “The jaguar⸺ the largest cat of the Americas⸺ is one of the archetypal creatures of Mexico, appearing throughout its mythology. The name of the magnificent city of Ek–Balam derives from Ek⸺meaning “black or star”⸺and balam, “jaguar”; thus, Black Jaguar or Star Jaguar,” writes David Stephen Callone in The Beats in Mexico. These are just facts, you can find them anywhere in the estranged world.

There is evidence that a jaguar nicknamed El Jefe, which lived in the southwestern United States from 2011 to 2015, preyed on a young American black bear sow. There is talk of formally reintroducing the jaguar into the American southwest, as Arizona and New Mexico have ample wild room for them. Its reintroduction (along with the Mexican wolf reintroduced successfully in 1998) would mean, just maybe, that we aren’t as estranged from each other as we think we are, that, in fact, with some effort, we still have wise hope⸺ the thought of the wildness of these two creatures in closer proximity to us is reason to believe in our innate goodness⸺ that we can unify, if the idea of working together to prevent the extinction of a species or two appeals to the better undomesticated angels of our nature. We can only hope.

As journalist/border author Bowden (author of Blood Orchid, Blues for Cannibals and Dreamland among others) noted in a 2004 interview, “So, basically, to bring them back is like bringing back the wolf in the Southwest, of which there were at most probably 2,000 before settlement. It’s a gesture towards restoring a kind of wild world that makes humans feel better.” Although, as he continues, “It is not a case of ecological management to make an ecosystem healthier.”

Activist and author Amy Irvine notes in her 2018 book, Desert Cabal, “Consider this: the wall which would be built not far from here, would not only keep out people but also jaguars, which have only just begun to pad their way back into Arizona after a long and grim hiatus. “

In January 2024, a jaguar was captured on trail camera footage in the Huachuca Mountains of southern Arizona. “We are watching jaguars reestablish themselves in the United States at a steady drum beat, in real time,” said Russ McSpadden, the Southwest Conservation Advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity in a recent article in Salon, recalling that the spotted cats have been trickling across the border since 2015. “It’s a beautiful thing… Jaguar habitat is threatened by proposed open-pit mines, transportation infrastructure and other massive developments as well as the growing threat of insurmountable border barriers. The jaguars we see in the United States are part of the same population as the jaguars we see in northern Mexico. These jaguars are part of one population that is, unfortunately, threatened by politics, nationalism and fearmongering. Connectivity is critical for wildlife.”

Bowden, when asked what non-profit organizations were most effective in dealing with wildlife issues in the southwest, he named the Northern Jaguar Project. Of course, he had the jaguar running through his veins, maybe El Jefe himself, consuming large quantities of mother bear and anything else that moved on this blighted, inferno of a ground. He died at 69 in 2014 in Las Cruces, New Mexico, down the road a few hours from where I live.

In his younger years, Bowden liked hiking for miles across the roadless Arizona border country and did so with impressionistic bravado; one particularly harrowing hike (with Bill Broyles) was documented in his 1986 book, Blue Desert. Their intoxicatingly treacherous walk across the desert was memorable for not only the existential threat of the June heat but the rattlesnakes and exhaustion as well. They were following migrant trails⸺ Bowden wanted to witness the journey firsthand. His prose reveals the Sonoran desert’s formidable beauty is as captivating as it is threatening. The hike is holy. The two young writers, near broiling temperature just north of the border, insist it so. He suggests, not at all plaintively, “We have entered the killing ground.”

Chuck crossed the border many times so the rest of us wouldn’t have to. There’s no evidence that the northern jaguar followed his tracks. Maybe he heard their lonely roar once or twice during all those years of wilderness trekking and camping. Yes, the jaguar is a symbol of that freedom, that camaraderie with ephemeral streams, remote tapestry walls and deserted, starlight-bewitched spaces. Somehow, somewhere under the night sky, they are kin. We are all kin. What Bowden brought back from his forays into the blue desert is spread out over two dozen books while much of what the jaguar can teach us is still a mystery⸺ I can imagine discoveries abound in those 56,000 acres of pristine wilderness in northern Mexico⸺ perhaps some of what we’ll find is what Bowden referred to as: “memories of the future.”

Perhaps he is speaking for the northern jaguar when he writes:

“I stare up, the stars are everywhere, there is no city on the horizon, the cold seeks my bones and no moon rises . . .”

Some of the tracks are hidden beneath the now overgrown paths that no longer lead to the old house⸺ it remains as we first found it: stoic, unclaimed, a hardened shell of an echo⸺ some tracks still lead in and out of endless war. The fresh ones share ground with the old ones; the echoes too, they were once everywhere. My ground has diminished somewhat without them.

The ghost of one of my dogs, for once, barked at nothing.

***

My father lived with us in Northern New Mexico for the first five years we were there before he passed away in his sleep at age eighty-five. Originally from Denver, he was a widower living in Glenwood Springs, Colorado where I moved in 1988 to start my own business. Before my mother died of alcoholism at sixty-seven, they thought they had found their magical mystery retirement home in the mountains, on the Roaring Fork River, near where it emptied into the still roaring Colorado.

There’s an old black and white snapshot on my bulletin board of my two uncles, my grandfather Carlie (a successful sheep rancher from Southern Wyoming⸺ so far south his ranch almost nudged the Colorado line), and my Pa, piggybacked on one of my uncles. A photo of joyful innocence, camaraderie, and probably a slightly soused vigor, taken not long after World War II. The black and white gods seemed playful that day, the fedoras blocked just enough of the sun to partially eclipse their faces. They all exhibited their dusty cowboy boots and baggy pants. They looked like a row of dusk broke horses. The range grasses seemed thick, no diluting the rain’s mercies; a stray ewe in the background. It was a day long before old age but after all their wars, except for my grandfather whose second son drowned in the Little Snake. But he smiles for the camera just as the moment separates itself from terrestrial time, as if gazing through something as porous as a dream catcher, as if no one asked, to quote Neruda, “how many people does our dead one weigh?”5

My grandmother, who had seven children and died shortly after giving birth to her last two daughters, was a forgotten headstone on a windy nearby hill. The prairie rolls up to it; my mother, who never knew her, was the summer passing over. We end up strangers after all. The tracks of family sometimes lead nowhere. The years are porous with the unforgiven, the past an angel who only drowned in the same river once.

During the war my father was a sailor. Grew up a trumpet player. His philtrum and, subsequently, embouchure, were damaged during a fight in his late twenties but he had that kind of glowing smile that inspired Irish tenors. Later in life he spoke about Millie, the girl he left behind in Denver but he married the girl from Baggs, Wyoming. Made a living during the era of interstate travelling salesman with leased car and expense account. To give me some room to breathe away from the nuns at Most Precious Blood Catholic School, he took me along during my summer breaks.

Clyde Barrow might’ve driven longer distances at one time but my father listened to jazz and swing on the car radio and tapped the steering wheel with his fraternity ringed finger. He occasionally sang as I stared red-faced out the window. Some nights he spoke too many companionable bourbons to the world. Had seen China and the Philippines but he loved the straight-arrow wide lonely flatness of Nebraska and its full yellow moons that guided him safely to his motel rooms, Best Westerns, after dark. One trip we paid our family’s respects at the stoic old graves of Hastings that had deliberated at their stations for far too long.

At home in the suburbs we didn’t speak jazz. We planted hearty rose bushes and snow shovels, Mission: Impossible and Vietnam on the tube. One bland Christmas, no snow. My first funeral was a horned lizard named Sylvester, then, my grandfather. One of my first memories was of my father joining some California beach boys as they pulled a burning fishing boat to shore with a tow rope, its Newport Beach skipper soaked in gasoline. I wasn’t allowed to probe the surf with so much as a toe after that. A couple of years later, family broke, he drove us to Colorado.

Newport, 1959.

Dinah Washington, Gerry Mulligan, Mahalia, Louis singing up the lazy river. I watch that old documentary, Jazz on a Summer’s Day through the stelae of years: a man with a freshly lit Cuban cigar snapping his fingers in some kind of ecstatic trance. Ah, the cool coiffed women! The colorful but quiet adjacent regatta! My father loved Louis Armstrong as much as anyone, how he gentled the world and gave permission to all the white folk to dig him because he promised

the music is forever

because his forever voice declared peace.

When I visualize jazz I hear wildflowers blooming. Memory accustomed to its own detonations and detours its capricious depths and tides. I imagine the two of us long ago, watching the movie from some seashore beyond ourselves, no silenced music from the grave, we’re together and worlds apart, I’ve grown up, my father became a grandfather, life wasn’t an ecstatic trance after all, but we settled on a summer’s day.

My father seemed to enjoy his last few remaining years out there with us. He was sometimes bemused, sometimes anxious; one time he compared the incomparable New Mexico sky with the blue of the ocean. Sometimes, he had a hard time navigating our rough terrain without assistance, but the dogs made him laugh. One spring and summer he would watch us work on our stone patio, just behind the house. It began at his deck and spread out several feet towards the garden. We scraped away the topsoil to make room for a layer of arroyo sand we hauled up in wheelbarrows. The floor of the patio was large, more or less flat sandstone slabs we initially stacked outside the back door. We then carefully rested the stones on the bed of sand, massaging them in place, making sure they were as level as possible, given the individual contours of each stone. We then filled each space between with mortar to secure them in place. Each stone possessed its own expressionless face, its own shades of brown, red and grey, its own heft and poise. On a summer’s morning I could feel each one’s radiant heat rising off the surface like an offering, a common planet remembrance of its past as part of a larger geologic event, sculpted by magma, deep underground. We shifted the shapes in our hands, the labor succumbing to ritual, to solving this puzzle and wondered, who produced this weight, who on earth belongs to this duende, this silence?

After my father passed, after we buried him in Denver next to my mother, I’d occasionally sit outside where he sat on his deck, and re-imagine the hours of stone work on that earthen patio, the fragile nature of his presence and how he once walked it, made a path of it, how his tracks remain with me⸺ I can feel his warmth, still.

If I was to take the measure of a place in my mind or in my relationship to its ground, I’d have to do so in the realm of its giving light, its presence in time and memory, its tracks, and in the things that it had selected to bestow on me, after twenty years, as I was leaving. Our old La Cantera remains, in most obvious ways, how we left it. Seemingly impervious to the change of seasons or families or one man’s semi-sentimental appraisal of how embedded in memory its character really is.

It was not a matter of rain, but time

END

Notes

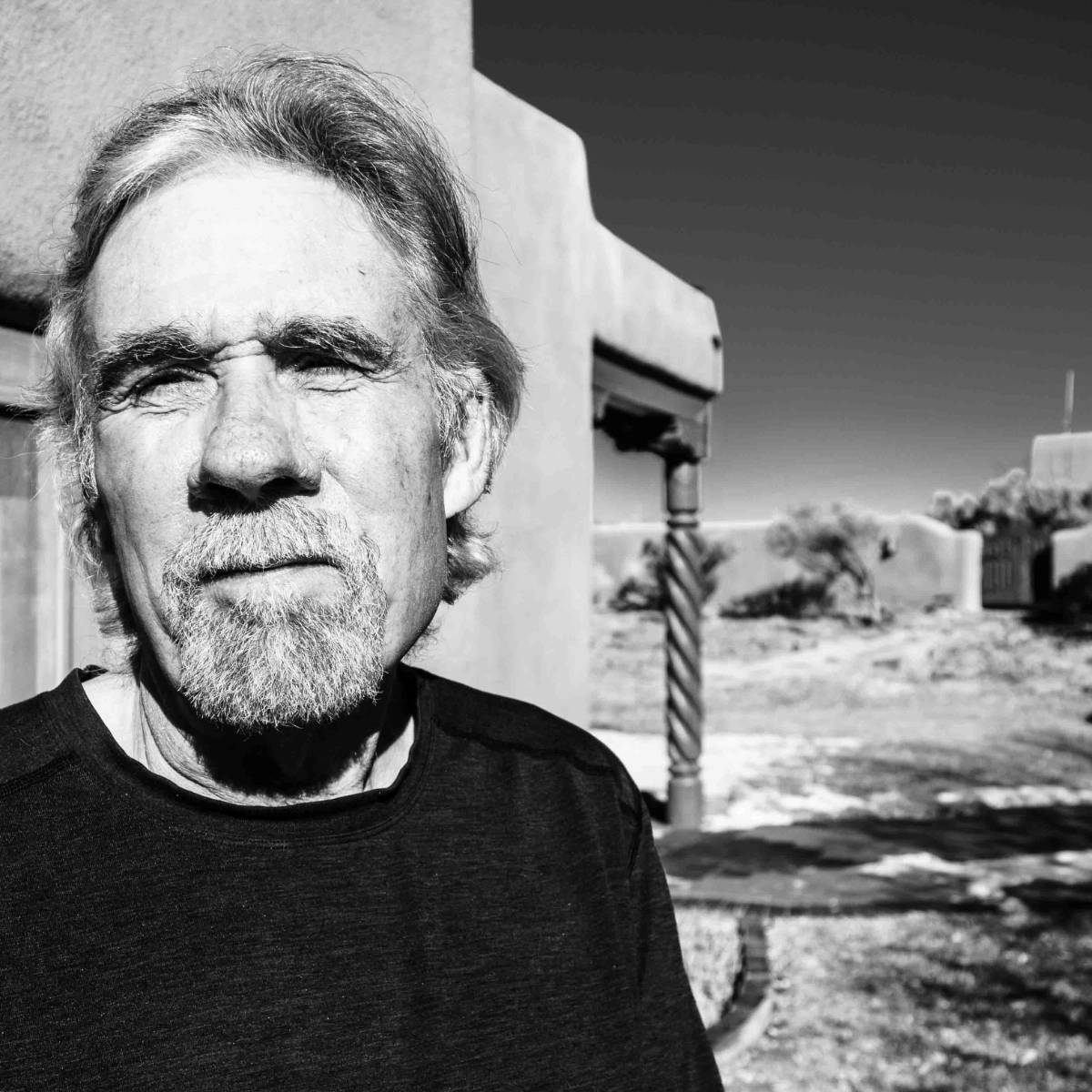

John Macker has lived in Northern New Mexico, near Santa Fe for 30 years. He’s the author most recently of Belated Mornings (poetry) and Desert Threnody (essays and short fiction) winner of the 2021 New Mexico/Arizona Book Award for fiction anthology.