A day before the long drive to Northampton, where I would join friends in a book talk about war and language, I arrived at a small town emergency room, signed in, took a seat, and for the next half hour mulled over what had led me there.

If you were to ask me how to rid a kitchen swarming with fruit flies I would tell you to put a tablespoon of baking soda into the center of a paper towel, fold the towel until it fits in the palm of your hand, place it in the sink drain, pour a half ounce of dish detergent on it, followed by an ounce of vinegar. Let it sit a few hours. Do this three times a day for three days and all will be well. But this time the annoyance continued. What to do? I descended to the basement, hoping the landlord kept a supply of sticky fly strips in the utility room. Hanging from a nail, I spied a small partly clear plastic bag with something in it. To read the label of whatever was inside I pushed the bag with the tip of my finger. Rat poison. No thanks. I went upstairs and made dinner. Did I remember to wash my hands? A while later I felt ill.

Even before my year of patrols, jungle, ambush, monsoon, when grunts screamed bloody murder, their rich dark blood blooming pure white cotton bandages that I slapped on, anxiety was my constant companion. From childhood to college I had nose bleeds. In grammar school, until the blood dried, at the first hint of trickling, at the sight of bright scarlet drops spotting white tissue, a school nurse offering much needed comfort, I experienced a child’s sense of panic. Vietnam—with its sudden firefights, ambushes, rocket and mortar attacks, a base overrun, the gunshot casualties howling my name—blood, everywhere blood—simply ramped things up. A half century later I have fewer nightmares where I’m hunted by NVA or Viet Cong, or my weapon is broken or misfires, or the bullets pour forth like molasses, or I thrill at killing the enemy. But I’m prone to worrying, to startle easily, and am hyperalert to sudden movements, sudden sounds. On any given day my moods are everywhere. I’m sensitive to caffeine. Sips of kombucha or espresso give me an energetic lift. And I walk four miles a day to soften my PTSD.

Now, feeling unwell, I began to worry. Several websites advised “drink plenty of fluids, call poison control.” I drank an entire bottle of kombucha, which only increased my fears.

I first experienced all-consuming dread in Vietnam. It is impossible to shake. Only afterward, when the screams and shouts and killing were done, when the moans and howling had quieted, medevacs inbound; for a very short time, a sort of weary paradise set in. Until once more we walk into them, or they walk into us, or we call in artillery, or they attack with mortars, or we blow the Claymores on their well-used trail—only then did the dread of violent extinction somewhat dissipate.

“Poison control,” said the older woman answering my call. Detecting the fear in my voice, she calmly stated, “Don’t worry. You’d have to eat the stuff for it to be serious. You’ll be okay.” For twenty minutes I busied myself with menial tasks, yet fueled by caffeine, my worrisome thoughts, “but if the symptoms persist you should visit the emergency room,” the woman had said. I called a cab, my heart pounding as I waited outside, knowing, in the back of my mind, this could all be for nothing.

At 9:20 PM five people were ahead of me. Thirty minutes later an ER nurse took my vitals. A half hour later I went to an exam room and lay on the gurney, a doctor would see me soon. Forty minutes later I walked to the nurses’ station.

“Do you know when I’ll be seen?”

The nurse said no doctor had been assigned, but “They know you’re here.” A half hour later he took my vitals. My blood pressure was 205 over 105.

“Do you have hypertension?” he asked.

“No.”

I didn’t mention caffeine. Or Vietnam.

“I have chest pains.”

They were likely related to exercise, but caffeinated, worrisome, I magnified every possible twinge. Not long afterward a doctor entered the room, listening attentively as I recalled the bothersome fruit flies, the tip of my finger pressed to a plastic bag that contained a harmful packet of rat poison.

Suppressing a grin, “It’s probably a low exposure,” she said. “I’ll order blood work.”

The nurse inserted a saline IV into my arm and administered an anti-nausea drug. He took three vials of my blood. He would repeat the process at 3 AM. A short middle-aged nurse wheeled in a machine to x-ray my chest. A tall nurse administered an EKG. For the next three hours I lapsed in and out of sleep. The nurse took blood. No long afterward the doctor arrived.

“Your lab work is normal. You’re free to go.”

A wave of relief washed over me. I checked my watch. It was 4:30 AM.

When I entered the cab, the driver, a large man with long shiny hair, in an ornery voice demanded, “I need fifteen dollars right now,” and he held out his large meaty paw.

Tired, hungry, wanting to go home, I paid him. Immediately we were friends.

“How long have you been driving cab?” I asked.

He took a deep breath. “Since 1986.”

Before that he drove tractor trailers. I assumed that meant good money.

“Not really,” he said. “Long hours, low pay.”

Before hauling freight, he worked eight years driving a trailer for a traveling carnival.

“I hauled the Umbrella ride,” he said, “The one that goes round and round.”

I had worked for an employment agency and asked if he set up, maintained, disassembled, and loaded the ride back onto the trailer.

“I did it all,” he said, “Took tickets. Operated. I did it all.”

One day he quit. When the owners asked why, he told them, “Eight years. No raises. You can shove it.”

As we neared my building the cabbie opined, “You know, it used to be you could turn left on red. There was a sign saying you could do that. But the sign is gone, or they changed the law, so you can’t turn left on red.”

As I exited the cab—it was close to five o’clock—“Have another wonderful day,” he said. There was irony in his voice, a hint of sadness too, as if he’d long relied on those four parting words to accommodate his lonely vagabond life. Did I mumble a reply? I don’t recall. He backed out the driveway, the birds in the trees just then waking. I ate breakfast. Slept a few hours. Packed.

The drive to Northampton took 3 ½ hours. Janet McIntosh, who teaches anthropology at Brandeis and is the author of Kill Talk (Oxford University Press 2025), drove; Dave Connolly, a Vietnam combat vet and poet sat up front. Throughout the trip we made small talk. I recalled that twenty-eight years ago I had lived in Northampton, not yet gentrified. Three decades later its prettified sidewalks crawled with fanciful restaurants, boutique cafes, high-end apparel stores, book, tea and gourmet shops, though the liberal policies that once embraced men and women down on their luck have spawned a homeless problem. Some long-time residents have moved out. We arrived in town close to 5 o’clock, meeting up with poets Doug Anderson and Preston Hood III. After a leisurely late lunch, we strolled to the art gallery where the reading would be held. By quarter of seven, only a handful of people had arrived. It looked to be a slow night, but by 7 o’clock every available seat in the spacious well-lit gallery was taken.

In 1967 poet, writer, English professor Doug Anderson was a Navy corpsman attached to a Marine rifle company in Vietnam. He stepped to the microphone and introduced Janet. Her audience-friendly talk described how training for war, and actual combat influence the language, thinking and actions of soldiers before, during and after battle. She spoke of the aftermath of war injuries, physical and otherwise, the innovative ways veterans, once transformed into “killable killers” have found to rebuild their psyches.

Next, Dave, Doug, Preston and I (each cited in Kill Talk) took turns, speaking a minute or two, then reading a poem which illustrated a theme in the book. Periodically, Janet commented on the language of our poems, how it referenced military training and culture, how GI slang dehumanized the enemy, how the rhetoric of duty, honor, country collides with the immorality of combat, furthering the GIs’ indecent idiom.

About half way through the reading, Janet asked Dave to read his poem “It Don’t Mean Nothing,” the title a GI phrase invoked to feign indifference to trauma, to the wars futility. Dave stepped to the mic. He is a confident reader. And he has read this poem, lived it aloud, too many times to count.

On his second day there,

they went down into Bien Hoa city

with their brand new guns,

just hours after the VC had left,

and strolled along a wide,

European style boulevard

lined with blossoming trees

and the bloating bodies

of Americans, dead for days.

He puzzled at their leader,

the nineteen year old veteran

with the pale, yellow skin,

bleached, rotting fatigues,

and crazy, crazy eyes,

who hawked brown phlegm

on each dead American saying,

“That don’t mean nothin;

y’hear me, meat?”

And everywhere he went,

there were more,

down all the days and nights,

all kinds of bodies,

ours, theirs, his,

until nothin meant nothin.

Certainly a tough act to follow. When Dave took his seat I adjusted the mic, took a breath.

“Jack Parente and I were in the same battalion in Vietnam, but we first met online. ‘Send me something you’ve written about combat. I’ll post it on my website, Medic in the Green Time. It has my writing and photographs, the poetry and prose of other Vietnam vets.’” I paused a moment. With the full authority of my voice I read Jack Parente’s “Song of the PFC.”

“We said it each day of our miserable lives. We said it when it rained, and when it didn’t rain. When it was hot. When it was hotter. It don’t mean nothin, we said. We said it because it sounded tough. We said it to keep from crying. We said it because it might be true. We said it at rest, and the bloodsucking insects swarmed, and our faces swelled, and our hands swelled, and our lips swelled, and our ears swelled, and we thought about getting malaria, and we thought about how good that would be—you get sick, you leave the boonies. Unless you died first.

“But the dream of laying asleep on a hospital cot, hot chow, no one shooting, made chancing a slow death easy. How bad could it be? It don’t mean nothin, we said. So we ditched the big orange pills; each day took the small ones. Skipping them won’t improve your odds, but when you’re dog-tired, anything beat humping the bush. But you don’t do it. You shut up and saddle up because it don’t mean nothin.

“We said it when dry sweat left white salt streaks on our stinking fatigues, worn five, six days, longer, until clean ones arrived. No tiger-stripes for us. Just the worn-out junk, grubby with mud, sweat, bug juice, gun lube, red-brown blotches from crushed leeches puffed up the size of ripe grapes with blood—our blood, some guy’s name tag stitched on the back pocket. The new ones ragged in a day, rotting in four. At night, wrapped in poncho liners on the jungle floor, we’d twist and turn in half-sleep between shifts on guard. At dawn, waking, a quart low, it don’t mean nothin, we said.

“We said it when a jeep filled with ammo exploded, killing eleven men. Said it when the mess tent took a direct hit. Don’t mean nothin we said after a sapper blew a bunker, the men inside pulped, burnt, crushed by sandbags and perforated steel plating.

“On a hilltop, taking AKs, mortars and RPGs, 175s too close for comfort, when they said you can’t retreat—just us twenty now, burned out, used up, wanting off that place that reeked of death—we thought for sure they’d pull us back. Instead, we stayed ten days, C Company boosting our ragged line. Bluffing our way past 12 dead, 26 wounded, we never spoke of it again. But who can forget the battle of Hill 54, just one more story too sad to tell, in a war that don’t mean nothin.”

Dave and Doug had seen heavy combat in Vietnam, I had seen my share. In 1970 Preston Hood III was a member of SEAL Team 2, tasked with covert dangerous missions. Before reading his poem Rung Sat, he set his cane aside, hushed his black lab service dog Gilroy, in his raspy voice said that to kill the enemy he lost part of himself. It became easy, he said. It didn’t matter. “Just like tying my shoes.”

I rappel through the door of the gunship

thinking about someone to love.

On patrol I’m a hunter in the blackness

dozing off, hardened, tired of danger,

I sight the enemy, waist deep in Rung Sat,

muscular legs standing executioner quiet,

black-green smudge & sweat curled on lip.

A snake stops me. I wade ahead,

fall through myself like a stone,

enemy voices passing only meters away,

the back drop of dark, life’s death.

I scan the horizon for movement,

count the bodies across the canal,

wait until they slip into the mud.

My mind is a red brown blur,

a gauze for the wounded we torture.

What’s happening seems not true.

Two hours before dawn the next day, we insert

by chopper, on some Viet Cong farmer’s land

to interrogate sympathizers,

& search for the mortar tubes

the NVA shell us with.

We demand revenge:

the smell of rice at the jungle top,

lazy orange mist shifting like smoke.

In low silhouette, we patrol to ambush —

our bodies surrounded by dark —

the shadow of surprise suspended inside us.

Across the trail, wind rips nipper palm,

fear crawling at our feet, a wounded man.

We radio in an air strike —

the wounded lie with the dying,

the dragged bodies hurried away

disappear into bamboo.

Blood trails along the river

mark a company retreat —

abandoned bombed-out bunkers,

shallow graves dug quickly,

brown-uniformed & black pajama bodies,

rice bowls & fish heads —

children half-buried in dirt.

2.

I am a man half in the water, half out;

my legs suck into mud.

My hands hold my head outstretched —

hasten to deliver me among the dead.

Mid poem Preston looked up. He’d begun the poem in Vietnam, he said, but thirty years would pass before it was finished. Thirty years struggling to understand the war. To come to terms with it. He recalled a firefight in Rung Sat, where he shot a teenage boy armed with an AK. Before he retreated, Preston jabbed the dying boy with morphine. Years later he wondered what compelled him to this act of mercy. “I didn’t want his death to be awful,” he said. “I think this was the first time, the only time I felt for the enemy. At that moment I turned back into a human being.”

I first met Preston, Doug and Dave twenty-five years ago at a William Joiner Center writers conference at UMass Boston, which is where I met Bao Ninh, the celebrated North Vietnamese veteran and author of The Sorrow of War. I would sometimes enter a not unpleasant trance when reading this story about a heavily drinking NVA veteran who seeks a way out of his hellish memories of combat through writing, and at the same time find his writer’s voice. Yet the author photo on the back cover, the face of the enemy we had daily hunted, and who fervently hunted us, unnerved me. I had seen that face, that black-haired, high cheekboned, implacable Asia face, dead, too many times. “And yet I wrote to Bao Ninh,” I said, using a turn at the mic to relate this experience, “and from Hanoi he sent me a Christmas card, wishing me well, hoping we might someday meet.

“On the first day, at the orientation…”

And I recalled sitting in an auditorium packed with aspiring writers; twenty yards to my right, five Vietnamese men waiting to be introduced. I couldn’t believe who I recognized among them. Afterward, as they walked single file to the exit at the rear of the room I jumped up, pushed past a gauntlet of legs and called out “Bao Ninh!” He turned around. From five meters we locked eyes. When I told him my name, “Moc Leby! Moc Leby!,” he shouted back. Astonished by this chance meeting, we rushed to each other with open arms. Ninh pulled me close, lifted me up, set me down, clapped my back once, twice three times, as if I were a human bell. I began to sob uncontrollably. Ninh took my hand and led me away.

“No…I’m all right,” I gasped, still sobbing.

Through Lady Borton, a translator and writer who’d given medical aid to both sides during the war, Ninh and I spoke briefly; we agreed to meet the next day. Sitting cross-legged beneath shade trees overlooking Boston Harbor we talked for two hours. My questions were academic: “What did you do in the war? What were the NVA tactics? What did your platoon talk about when not in combat? What were your feelings about the Communist party?” Ninh was thoughtful; patient in his replies.

Finally, I asked, “Is there anything I’ve overlooked? Is there anything you want to add?”

“Yes,” he said, leaning forward, eyes narrowing. “The NVA were not robots. We were human beings. That is what you must tell people. We were human beings.”

I felt foolish, recalling too late that Ninh had spent six years in the Glorious 27th Youth Brigade. Out of five hundred men and women, ten survived.

We stood up, dusted ourselves off, shook hands, headed back to campus. When Ninh stopped to smoke a cigarette I delved into my wallet for the small photo of my platoon which I’d carried for thirty years. On the back of it I wrote, “To Bao Ninh, these good men meant as much to me as yours did to you.” He held the photo in the palm of his hand, contemplating the young Americans with their steel helmets, sun bleached uniforms, hand grenades, bandoleers of ammo and M16s. Looking up, his face inscrutable, “How many dead?” he asked. “Only a few,” I answered. “Many wounded.” Ninh tucked the photo into his shirt pocket. We headed to the student cafeteria. Each time I tell this story it happens within me. I think of it as a turning point.

Doug Anderson is the author of the poetry collections The Moon Reflected Fire, Horse Medicine, Blues for Unemployed Secret Police, Undress, She Said, and the memoir, Keep Your Head Down. He has received numerous honors and awards. Stepping to the mic, before reading his poem “Killing With a Name” Doug explained the origins of the word “gook,” a racial slur to dehumanize the enemy traced to the 1899 American war in the Philippines. GIs used the same word in Vietnam. The Vietnamese phrase “xin loi,” means “I’m sorry.” But American troops pronounced it sardonically. A grunt gets killed, somebody says “xin loi.” Someone loses an arm. “Xin loi.”

We were taught to call the enemy gook,

slope, dink, and worse,

because it’s easier to kill

that way, easier to sleep at night

if you’ve merely crushed a roach

under your boot heel,

sprayed poison down some hole,

or set a whole village on fire

to kill its vermin. But when we

dragged that guy out of the hole

and stood him up, and he blinked

in the glare—all five feet of him

covered in mud so even his

black pajamas were gray with it

he didn’t look like anything

you’d want to kill

in spite of his being a tough little shit,

taking round after mortar round,

rocket after rocket

and still firing back at us while his

squad slithered through the leaves

and got away.

He just stood there, maybe hoping

for a quick death, just a shot

to the back of the head,

no interrogator to slip a hat pin under his nail.

I knew then I couldn’t say gook again,

could not joke

about burning the poisoned land

where, for reasons

that grow dimmer every year

we were sent to fight a war.

And so it went. Proceeding smoothly, each man at his turn talking a bit, reciting a poem, Janet offering commentary. When the subject of war humor came up I stood and recalled how Vietnam combat vet and journalist Tony Swindell and I, thinking a book was at hand, asked combat veterans to send us their best war jokes. Not polite gags, mind you, but clever obscene jests that mocked death, shrugged numbly to survive it. Even so, we received just a handful which made war grimly comical. We abandoned the book, but posted the winning jokes on my website. “This joke,” I said, “was submitted by former lieutenant Fred Tomesello, author of Walking Wounded, Memoir of a Combat Veteran.”

“After an attack on the Cam Lo District Headquarters my platoon was tasked with counting the enemy dead and wounded. I assigned the job to Frenchy’s fire team. Artillery had butchered the bodies. Heads, many still wearing helmets, were separated from torsos. Arms and legs were strewn all over the battlefield. The NVA had dug shallow trenches under the barbed wire and used sand, trying to cover their dead. “Goddamn, they’re all fucked up,” one of Frenchy’s men complains. “They’re probably booby trapped too! I ain’t touching any dead gooks.” Frenchy shoves him in the chest and yells, “What the fuck’s wrong with you? You chicken-shit or something? Here! Here’s how you do it.” Frenchy grabs an ankle sticking up from a shallow grave and tugs as hard as he can. The soldiers body jerks out of the ditch, his other leg flops behind him and the leg that Frenchy’s holding snaps from the body. Frenchy holds the leg up at me and smiles

“Hey, Lieutenant, he says, “Lets grab one leg each and make a wish!”

The audience cringed, though when I first read this joke I could not stop laughing.

If we’d had time I’d have reminisced the night in Cambodia I dreamt the enemy was crawling past. Waking, I nearly shot the man next to me. Seeing his American boots, I pointed my pistol straight up, pinched the hammer, pulled the trigger, set the hammer to place, re-holstered, returned to sleep. Twenty-eight years later I admitted to him what nearly happened. “Gee Doc,” he said, “I’m glad you didn’t shoot. It would have put a dent in my golf game.”

We both laughed, but I cried, too.

And cried with rage when my folks, emotionally unwell, refused to send me a survival knife. K-bars they’re called, large sturdy daggers, good for any number of things in combat. “We don’t think it’s a good idea,” my mother wrote. “You might hurt yourself.” Hearing that tale over Thanksgiving dinner my uncle roared with laughter. Even then the folks didn’t get it.

Dave Connolly might have recalled Sergeant Rock, his pet monkey that shit in its hand and hurled the feces at people it did not like. The beloved monkey was shot by MPs.

Preston Hood might have relived the day two handcuffed VC led his SEAL team toward an NVA rally point. When the SEALs were ambushed their machine gunner opened fire, screaming “Rats ass bats ass dirty old twat 69 assholes tied in a knot. Eat suck fuck bite nibble gobble chew. I’m a fucking frog man! Who the fuck are you?” In the few seconds the bewildered enemy did not return fire the outnumbered SEALS, laughing, made good their escape. I’m sure Navy corpsman Doug Anderson could have spun a few happy tales too.

After a final round of poems Janet made closing remarks. The audience warmly applauded. Before departing, we chatted with well wishers. A Holocaust Studies professor, bearing an uncanny likeness to the comedian Jack Benny, spoke with immense feeling, animating his thoughts by swaying his hips, arms, hands, in a sort New England hula, or Judaic Tai Chi. An elegant college classmate of Doug’s expressed her deep appreciation for the event. A middle-aged woman wearing a faded schmata and necklace, from which hung an impressive antique Sheriff’s badge, came near. I wondered about the badge but did not ask. She complimented the reading, then launched into an urgent litany of her many attainments and travails. Among them, she had been arrested for making terroristic threats.

“The case went to the Supreme Court. The charges were false. The prosecutor was corrupt. I won!” she said.

“Is that so?” I replied.

“You can Google it,” she said.

Before we parted she expressed an interest in my website. With trepidation I gave her my card. A few days later I received her rambling email. Attached were her 5-page resume, screen shots of her website, the covers of her many published books.

“If you’re ever in Northampton again I’d love to see you!”

I googled her. Arrested for threatening to shoot a colleague, she was sentenced to three months in prison. Released on bail, re-arrested for violating parole, evaluated at a psychiatric facility, she was deemed unfit to stand trial. The charges, dropped from felony to misdemeanor, were dismissed. I suppose you could say I dodged a bullet.

Around 8 PM, as Janet, Dave and I headed out for dinner, I heard Preston say that many in the audience were moved to tears. I wondered, were they touched by Dave’s unsparing elegies, his stark lyric grieving? Were they moved by Doug Anderson’s poetic gift for rendering obscenities beautiful? Or Preston’s heartfelt rebuttal, that what he, what we survived had meaning. Or my affecting encounter with Bao Ninh? Janet’s splendid commentaries? Together we had not praised or glorified combat, but imparted, as best we could, its profound awfulness, and ways to transform it into something useful.

Unlike Dave, wounded by shrapnel and bone fragments from the man in front of him, or Doug and Preston, both Purple Heart recipients, the four of us fluent in PTSD, my only physical wound is invisible. The first enemy grenade twisted the machine gun in half. The second landed between us. The pointman, machine gunner, a riflemen, the radio man, with nowhere to hide, threw themselves atop me, Wilson last on the pile—BOOM—getting it worst.

Age and the blast have dulled my hearing, yet at each restaurant we entered I was overwhelmed by the harsh glaring lights, the piercing metallic noise. “I’m sorry,” I said. “I can’t be here.” At the fourth restaurant I thanked Dave and Janet for indulging me.

That night we stayed at Janet’s sisters house, her sister being away.

“She travels a lot,” said Janet. “She collects things too.”

Janet wasn’t kidding. Tightly bunched inside every kitchen cabinet were multiple packets, boxes, bottles of every sauce, spice, ingredient. Shelves were chockablock with assorted ceramic mugs; drawers teemed with silverware, a glut of utensils. Ranged throughout the two-story, three-bedroom house were uncountable pairs of shoes, assorted coats and sweaters, piled sheets, folded towels, an enormous collection of carry-all bags, rolls of fabric, balls of yarn, books, magazines, journals.

Janet made cocoa. She fed the cats, Snuggles and Tiger, and after a time led us up the narrow staircase to our rooms.

I slept well that night, though it was not always so. In college I kept a loaded .25 automatic beneath my pillow, a canteen of water beside the bed. What happened to the pistol I don’t recall. For years I kept a machete shoved beneath the mattress, the handle within reach. Then a meat cleaver. Then nothing, though the bedroom door must be locked, and I must face that door.I’m told that’s par for the course.

The next morning I didn’t bother to shower. In Vietnam my unit once spent three months in the bush. “114 days Doc,” said the lieutenant, whom I visited in 1999. Filthy and wet, each morning my squad sat hunched on their helmets, poncho liners pulled ‘round like serapes, trapping the pitiful warmth from fuel tabs lodged at our feet. Plumes of foul steam rose from our bodies. Soon, one man to the next, tormented by tinea cruris, bid me, “Doc, can you wash my back?” With a bit of soap and water, a bit of gauze, I did that, and each day tended their cuts and scratches, their head and belly aches, fevers and pains. And when the pointman or machine gunner, the RTO or rifleman screamed or moaned “medic,” I ran, crawled or stumbled toward them. “Medic,” they cried, and I did my best to care for them. Will always care. Will always be their medic.

Early the next morning, before the long drive to Boston, Dave and I chatted in the small musty living room crammed with bookcases, a large antique bureau, two oak tables, an armoire, a very used sofa, three sadly upholstered chairs, a rarely used treadmill, a rarely played baby grand. For some reason I asked Dave if he’d experienced anything supernatural in Vietnam, similar to our friend Gary Rafferty, who once saw a white light engulf two men waiting to depart a besieged firebase near the Laotian border. Their fate, he realized, was sealed. A few minutes after their truck lurched forward, an enemy artillery shell whistled overhead, seconds later exploded, a direct hit on the truck. “Gary,” I said, “You have got to write that down.” And he did, including the story in his memoir, “Nothing Left to Drag Home: The Siege of Lao Bao as Told by an Artilleryman Who Survived It,” which I edited.

Dave told me such a remarkable story that when Janet ventured downstairs I begged him to repeat it to her.

Ever the anthropologist, Janet asked permission to record.

“Yes, we said.”

Dave leaned forward. “My grandmother was born under a caul. It didn’t slough off at birth. When she was a girl she could see and hear things. She told people their fortunes. She told the mailman, ‘Put your affairs in order. You can go to a hospital, but it won’t matter. You’re a dead man.’ He had a cerebral hemorrhage a couple of days later.”

After his grandmother’s stroke and advancing senility Dave helped care for her. She took to calling him Peter, the name of her brother who’d been killed in childhood, kicked in the head by a horse. She called him Peter for months. Once, when he was 15, his grandmother woke him in the middle of the night. “David,”—as she spoke the hair on the back of his neck stood up—“you’re going to go to war like your father. You’re going to get hurt, but not as bad. But I see two flashes of light and something whipping in the darkness. And when you see that, the danger is behind you.” Dave had no idea what she meant.

Three years later, with the 11th Armored Cavalry, he found himself on a firebase in Vietnam, living on the bunker line, where his unit stayed until they returned to the bush. One day, sitting in a jeep with an officer, as Dave looked down the perimeter road at all the bunkers, suddenly, bang, bang, a bunker was hit by two rockets. As Dave rushed to the collapsed shelter, the two men inside struggling to free themselves, he looked up to see the commo wire, strung between bunkers, wildly waving up and down. Here were the two flashes of light, the whipping motion in darkness. “LT,” he said, “call out the reaction force. Call them because they’re behind us.” “How do you know,” asked the lieutenant. Dave almost bit his tongue. “When I was 15 my grandmother told me this is exactly what would happen.”

One morning, home on leave after his first tour, Dave’s grandmother died. She was waiting for him; then as now, she talked to him in his deaf left ear. “Lanny, Lanny,” she calls her grandson, which is sweetheart in Irish, “there are times not to be afraid.” Sometimes she comments on ordinary things; the weather, what a beautiful day it is.

Years ago Dave and his three sisters consulted a medium. “Who are you?” she asked Dave. He identified himself. The medium said his son’s name was Jake, which was true. She thought they were fighting over Jake. “But it’s you they’re fighting over. Caddy and Flo. They’re fighting over you. Caddy is saying, ‘He’s my boy. He’s always been my boy.’” Cady was Dave’s grandmother. Flo, his mom.

Like his grandmother, Dave has known things before they happen. Four or five times in Vietnam he stepped off a trail which seemed alive with death. He didn’t know why, but it did. It’s the reason he’s the last man alive from his platoon.

Before heading back to town Janet fed the cats. But where were they? Throughout the night black Snuggles, dark grey Tiger freely roamed the house. Janet and I searched myriad nooks and crannies, under the sofa and chairs, the shadowy world beneath the baby grand.

“Here kitty kitty…”

Had they escaped out the side door as Janet watered the riotous front lawn, the haphazardly beautiful garden?

“My sister will kill me,” she said, before running upstairs, frantically probing each cluttered bedroom and jammed full closet.

“Here they are!” I shouted.

Sitting atop a bookcase, merged with the dark wall paper, the dim light, the felines, except for their bright yellow eyes were barely visible. Janet sighed with relief.

We drove to town, at a popular café met up with Doug, Preston and his partner Kathy where we chatted and ate well. After saying our goodbyes, with Janet at the helm, Dave riding shotgun, the medic behind him, we began the long drive back to Boston. “Back to the world,” we said when leaving Vietnam. But all that, I tell myself, was quite some time ago. Hopefully the fruit flies were long gone too.

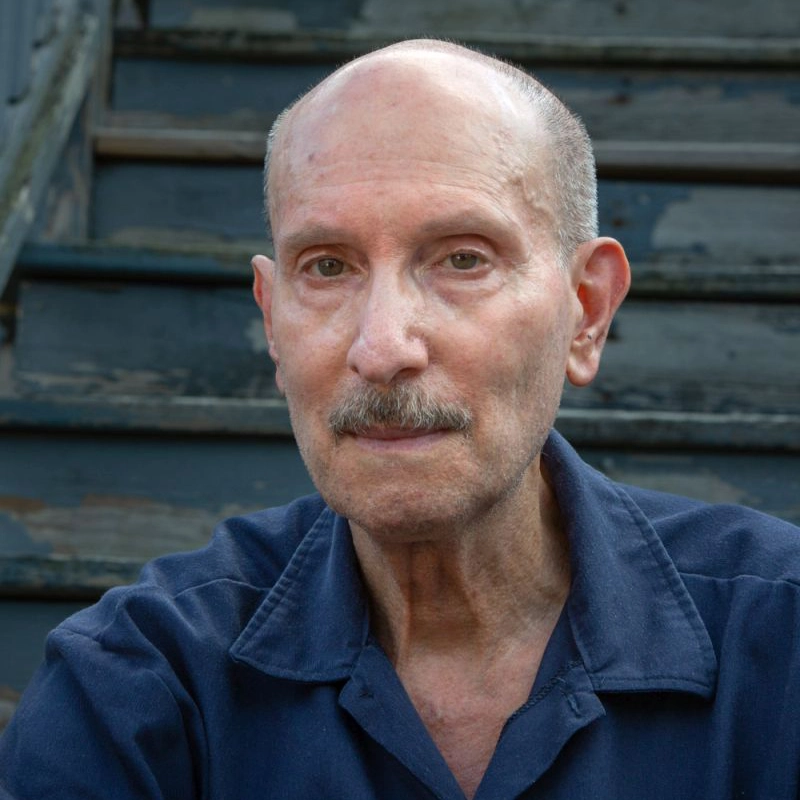

Marc Levy served as an infantry medic with the First Cavalry Division in Vietnam and Cambodia in 1970. His writing has appeared in War, Literature and the Arts, New Millennium Writings, Cutthroat, Slant,The Westchester Review, CounterPunch,Gargoyle, Pangyrus, Litro, Panorama Travel Journal, Queen’s Quarterly and elsewhere. He has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize.