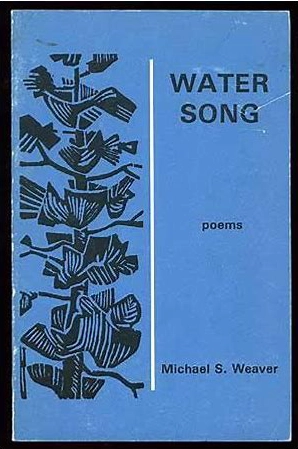

Water Song

by Afaa Michael S. Weaver

University Press of Virginia, 1985

73 pages

ISBN: 0-912759-05-4

Almost forty years ago I promised to write a book review. James Taylor – no, not that James Taylor, but the guy from Baltimore who headed Dolphin-Moon Press, my publisher at the time – told me that the author of the book, Michael S. Weaver (as he was known then), would be the next big thing in the poetry world, that Michael would be going very, very far. This was back in the late 1980s and I was fully intending on writing a review of Weaver’s first book, Water Song. Mike was a friend of James’s so I wanted to try to help both of them. Aside from wanting to write the review, I was also running a reading series in Boston, at the Cambridge Y under the name of James’s publishing house. I was trying to promote an out-of-town and out-of-state press in Boston’s narrow small press publishing circle.

So, as part of this promotional effort, I invited Mike to come up and read. And he eagerly and gladly assented, paying for his own train fare from Baltimore. Least I could do was put him up at my apartment and feed him. (I’m sure I whipped up some sort of pasta dinner for him.)

When I met Mike at South Station I was struck by his physical presence. He was not only the next big thing in the poetry world, but he was an immense man – tall, broad shoulders, a football lineman’s physique. Someone who commanded attention but in a very quiet way. He seemed hewn from stone and had a smile that could stretch all the way from Baltimore to Boston. Mike was excited, not only from being asked to read in the great literary center of Boston, but from the fact that he had the great grace and good fortune to meet his idol, August Wilson, on the train north. He was positively beaming from that encounter, that wonderful, life-affirming serendipity.

I don’t remember who I paired Mike with – usually I had a poet read with a fiction writer, mixing genres. But I felt supremely embarrassed on behalf of the Boston poetry world when only three people showed up for the reading. The other reader, it seemed, was no help in being a draw. Michael had coughed up his train fare and took time off, and I could only garner him three faces in the crowd. At least there were three. I had read his book and was blown away. James, always the showman, was not overstating here. I imagine if anyone had read Water Song, I’m certain they would have made it imperative to hear him read from that book. In retrospect, I guess that’s where a review was needed.

I apologized profusely to Mike. I invoked a curse on what I felt was a distinct provinciality evidenced in the Boston poetry scene that didn’t think anyone writing outside of Boston merited attention.

But now, with nigh forty years of hindsight, it’s time to take another look at Water Song. It’s also time to bring my apology full circle. Both procrastination (a severe personal defect) and inability to find a venue that would carry a review of the book conspired to derail my promise. So I need to make good there as well.

In re-reading the poems after setting aside the book for so many years what appears most striking to me is the prevailing sense of drama throughout the book. Attesting to Weaver’s high estimation of Wilson, the pull of drama – literally, the acting out of hopes and dreams on the stage before a rapt audience – is everywhere evident in Mike’s poems. It’s inescapable. On another level, Water Song evokes Thorton Wilder’s Our Town, but in a way that easily goes beyond Wilder’s hopes and dreams. The poet’s voice in Water Song has become the stage manager’s but in every way Weaver had transformed and elevated that character. Weaver has evoked that reference and then exceeded it, in many ways becoming the alchemical poet transmuting narrative lead into gold.

One has the strong sense of the poet ambling in from the wings and taking a chair and settling down. You can hear the inhalation and exhalation of breath before he utters a word. The poet relates the tales and happenings of his town – Baltimore – as you can see the characters pantomime in the background of the stage, one spotlight on the seated poet, the other roaming among the assorted characters behind him.

In reading the poems in Water Song, the “audience” (or reader) not only sees the characters interact among themselves, but also the audience can inhabit those characters as the poet’s voice relates the inner workings of their thoughts and emotions. What things are being conveyed are place, time and character. What each character experiences, including and beyond the violations of racism and misogyny, the reader – that audience – also directly experiences. The poet relates, not with criticism or irony, but with love and respect. In “In the Evening Shade,” the poet regales us with the diorama of his family. We witness the family struggling and the poet ends his intimate portrayal with:

“…Jesus said you gain nothing

when you lose your soul trying to get rich, and that’s what

I mean. I would rather starve as long as we do it with all

my children here with us…”

The poet, with his choice of words and details, gives voice to the dance of the family he recounts to us. He does not forget and does not let the audience forget. He makes their movements and their spirits spring alive – a fortress against an enveloping silence. The title poem “Water Song” ends with:

“In the house that has died…

Grandaddy sits in his corner…

in… the dark, moving silence around this world.”

In the alternating stanzas of “Currents,” we listen to the articulations of the neighborhoods in Baltimore, and the faces that move among them. We can almost see the theater, the drama unfold behind the poet, as each stanza seems to reflect different tableaux – one on one side of the stage, the next stanza on the other, with the spotlight illuminating alternate wings of the stage. The stories flow almost like a river until we are swept “close to Earth, earning grace with sacrifice.”

Aside from the scenes of intimate and impactful drama in Water Song, or maybe integral with that sense, is a seasoned prescience. One hears the vibrancy of youth as well as the deep well of wisdom (both from a person’s accumulated years and the accumulation of history) coming from Weaver’s poems. The unique combination of soothsaying and truth saying – that admixture of future, present and past – dwells within these poems, “passing through the waiting time, conspiring to cheat death.” These poems presage Michael being conferred the Ibo name “Afaa” – which means oracle. One listens to a voice with a wisdom beyond its years, who sees much – too much – but, despite the weariness inherent in that vision, is not too tired to wear an expression of hope and joy, the smile of knowing enough and not wanting to turn away, to continue that “slow walk through the waiting time.”

Forty years later, Water Song affirms one of the strongest and most generous voices of American poetry. The prophecy has held: Afaa is a force to be reckoned with and heeded. Much has happened, and we benefit greatly from what he has seen and sung.

Gian Lombardo taught publishing for 23 years at Emerson College in Boston, Massachusetts. He directs Quale Press, which mainly publishes prose poetry. His books include the prose poetry collections Start of Something Beautiful (2023), Bricked Bats (2021), Machines We Have Built (2014), Who Lets Go First (2010), Aid & A Bet (2008), Of All the Corners to Forget (2004), Sky Open Again (1997), Before Arguable Answers (1993), and Standing Room (1989), as well as the poetry collection Between Islands (1984). In 2022, his translation of Louis Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit: Fantasies in the Manner of Rembrandt and Callot appeared. Other of his translations include Michel Delville’s Anything & Everything (2016), Archestratos’s Gastrology or Life of Pleasure or Study of the Belly or Inquiry Into Dinner (2009), Michel Delville’s Third Body (2009) and Eugène Savitzkaya’s Rules of Solitude (2004).