PART 1: A Period of Adjustment

Two weeks after Roger Pratt graduated from Georgetown Law School in Washington DC, he and his fiancé Joyce Johnson, drove back to their hometown of Chicago in a modest, rented van with a few boxes of clothes and other belongings. They had lived in separate apartments during their nearly two years of DC courtship, so the flat they secured via landline telephone (this was back in 2005 when things were still conducted that way) would be the first time they’d be residing under the same roof.

The building was in Lincoln Park, on the North Side of the city and adjacent to Lake Michigan, the neighborhood just as toney as the ones where they’d lived while in DC—Joyce Capitol Hill, Roger DuPont Circle. (Lincoln Park was also a long way from Parkland, the Far South Side African American enclave where Joyce and Roger had grown up; an hour’s drive at least in good daytime traffic, which the couple hoped would prevent relatives from dropping by unannounced.)

The building they moved into was an eighty-some year-old structure with outer walls of maroon brick, three stories high with four units per floor. The hallways were tidy, with thick rug runners on the creaky stairs and landings that were illuminated by a wide skylight.

Joyce and Roger’s snug quarters were on the top floor. There was a kitchen of sorts set along a wall—fridge, countertop, stove, more countertop, sink—that was directly opposite the street-side wall which had a pair of wide windows, easily the place’s best feature, the portals facing west which allowed for abundant sunlight on cloudless evenings. A bedroom off the living room/kitchen had just enough space for a queen-size bed and a dresser. A bathroom with a claw foot tub and a den the size of a walk-in pantry completed the layout.

After a wedding night spent at a downtown hotel, they returned to begin married life together. They were postponing a honeymoon because Roger had to take courses in preparation for the Illinois bar exam. These prep courses were five and six days a week. Lectures and workshops that started at nine a.m. and sometimes ran as late as mid-afternoon. Roger took public transportation downtown, leaving Joyce to handle the unpacking of their stuff. When he returned home in the late afternoons, after a quick supper and some conversation, he was back at the books. This home studying was done in the teeny den, he sitting on an old, dinged, school house chair at a scuffed, wooden desk; both items bought second-hand. The room had no window, Roger reading by the light of a banker’s lamp. On really hot evenings and nights, he often sat bare-chested in a pair of cargo shorts, the only cooling comfort provided by a square-framed fan that produced a not unpleasant drone.

On a few occasions Joyce put her foot down, all work and no play etcetera, etcetera. She insisted they take advantage of Lincoln Park’s amenities—live theater and music performances, farmers’ markets, street fairs, and lakefront strolls amongst all the bikers and runners and rollerbladers. As with DC, they found Lincoln Park people to be friendly for the most part. None of these friends were Black because Lincoln Park didn’t have very many Black people. Which didn’t bother the couple. After their years in college and DC, they had unconsciously grown accustomed to such demographics.

The routine of daily hard study punctuated by the occasional afternoon or evening off, lasted six weeks. For Roger, much of it would later be a blur in his memory, while Joyce would remember it as a bittersweet time. She was happy to be finally living as wife and husband with Roger, but being alone most of the day, then seldom interacting with him when he was home, left her feeling lonely. These feelings she kept to herself, not wanting to add to Roger’s anxiety. He was scheduled to start with the firm in September, but the test results wouldn’t come until October. “I can’t start work and flunk the bar, Joyce.”

The two-day bar exam was at the end of July, after which Joyce and Roger finally got to go on their honeymoon. Roger slept nearly the entire flight to Hawaii, then slept for significant parts of the first days they were there, Joyce passing away this down time by watching TV or gazing from their room’s high balcony to the blue sea and crowded beach, a view they’d paid a premium price for. As a result, although Joyce had fun with Roger their last three days in the islands, but when they got home, she did not feel as good about the trip as she might have, recalling, with some bitterness, the sight of Roger sprawled across the hotel bed on a perfectly wonderful afternoon.

And as if that weren’t bad enough, upon their arrival home, less than an hour after they dropped their suitcases inside the apartment door, Mrs. Pratt called Roger. She asked how their trip had gone. Roger gave her a brief summary. After which Mrs. P informed him that she was starting a new family tradition—Sunday suppers. And that he and Joyce had a standing invitation to, “come break bread with me and your father.”

She then explained she had not made the offer earlier in the summer because she knew how busy Roger was studying for the bar. But now that the exam was done and he and Joyce were home from Hawaii, he’d have lots of free time between now and when he started work. In conclusion, she added that Joyce’s mother was of course, also welcome.

Caught off guard, Roger told his mom he and Joyce would be happy to come.

“Happy to do what?” Joyce asked when Roger was done talking on the phone. When he told her what he had agreed to, Joyce viscerally responded with, “Why’d you tell her that?”

Roger, sounding defensive, said his mother had surprised him with the invite and he hadn’t time to think of an excuse, to which Joyce again viscerally responded. This time with: “How about, ‘Sorry, Mom, but I need to spend both days of the weekends with my wife.’” And before Roger could voice any response to that, she went on to say she didn’t want every one of their Sundays “eaten up” because if they went to Parkland to visit his folks, they’d have to visit her mom too.

When Roger said his mother had extended an invitation to Mrs. Johnson as well, Joyce dismissed that with a wave of the hand. “Momma won’t come. She doesn’t like your mother. As you well know. What my mother will do, is make sure we spend just as much time at her house as we spend with your parents. You add in the time it’ll take for a roundtrip drive between here and Parkland, we won’t be back home on Sundays until nine o’clock.”

Roger thought Joyce was exaggerating on that last point, and it showed in his voice when he threw up his hands and said that he didn’t want to spend all-day Sunday in Parkland either. “I’ll just tell mom that I should have spoken with you before I agreed to—”

“No,” said Joyce cutting him off. “That’ll make me look like the bad guy.”

“But you just made it clear you don’t want to go.”

“And you,” said Joyce pointing a forefinger at him, “just made it clear that you don’t want to go either. Which means you have to call your mother back on the phone and tell her that spending Sundays with you and your daddy isn’t going to work, for you.”

Roger, conceding defeat, shook his head a couple of times to show her that he understood. Joyce then pressed her victory by saying, in a tone Roger heard as a tad condescending: “Can we agree from here on that I don’t finalize any social plans for us without checking with you first, and you don’t make any without checking with me. Okay?”

“Okay.”

“I mean,” said Joyce, pressing on, “we’re married now. And you promised me, you promised, that we would have this month all for ourselves.”

Roger actually did not remember promising any such thing, but he also didn’t doubt that he had done so. He frequently forgot verbal agreements he made with Joyce, who had a steel-trap of a memory that seemed to forget nothing. Nonetheless, he was still irritated and in an even, but definitely, “enough already” tone, he said. “I hear you. I hear you.”

Joyce didn’t let up. “So, you’re going to call your mom back today and tell her?”

Roger looking her in the eye now, gestured with his open hands like he was lightly shoving at something. “I said, ‘yes’, Joyce.” And she turned away, both realizing that here they were, not a full day back from their honeymoon, and having their first ever serious argument.

Mrs. Pratt was most put out when Roger called her back later that day and said he and Joyce wouldn’t be able to make any Sunday suppers that month.

“I may not have a lot of Sundays free once I start work this fall.”

“You two can’t even come once this month?” she said.

“Ma, I just got married. I want to spend as much time as I can with my wife. Just the two of us.”

“Well, I sure hope this doesn’t mean I’ll never see you again.” Delivering a curt goodbye, Mrs. Pratt disconnected the call.

Turning to her husband, who was sitting nearby smoking a pipe and reading the paper, Mrs. Pratt said, “Roger and Joyce aren’t coming to any of my Sunday suppers this month.”

“So I gathered,” he said evenly, not taking his eyes off the sports section.

“I’m telling you right now,” she continued, “as sure as my last name is Pratt, it was Joyce who put Roger up to this. What good is having him back in Chicago if he’s not going to spend time with his family?”

Eyes still on the paper, Mr. Pratt said calmly, “Roger is married. Joyce is his family now. Same as how you became my family when we got hitched.”

More cross than she already was, Mrs. Pratt said: “Why is it you can never take my side?”

This might have been the end of it, but by evening, Joyce was having second thoughts about her earlier demand. Her tendency was to grow lenient after a disagreement, and so, that evening, she told Roger he should call his mother again and tell her they could make one of the Sunday suppers that month. Roger, recognizing a major concession when he saw one, thanked Joyce and immediately phoned his mom.

Standing at the kitchen sink, washing the dinner dishes, listening to Roger on the nearby couch behind her as he chatted happily with Mother Pratt, Joyce was struck, as she often was after making a concession, that she’d perhaps conceded too much, that she should have stood her ground, that conceding here only was setting her up for a future disappointment.

This theory was borne out, or so it seemed to Joyce, the very next day when in the early evening, as she stood at the kitchen-wall stove cooking, Roger arrived home with what looked like a heavily weighted canvas tote bag.

“What’s all that?” she said, gesturing at the gray bag with a gravy-coated, wooden spoon.

“Just some light studying,” he said, like it was no big deal.

With an expression of apprehensive curiosity, she said: “Studying?”

Still maintaining his, “no big deal” demeanor, he said, “Yeah. Mergers and Acquisitions.”

Way angrier than she’d been the day before, Joyce said: “Aw, c’mon, Roger.”

And here, there’s need for a bit of backstory.

In August of the previous year, at the end of Roger’s summer associate’s term, when the firm he was working at had made him a formal offer, he was told he’d be starting in the Mergers and Acquisitions practice group. This despite his summer tour having been with the tax law group, tax law being his primary interest. (Environmental law was his second.) At the offer interview, the equity partner who had managed the associate’s program, a not unfriendly White guy with bushy eyebrows and a longish face, had told Roger: “We have to put you where we think we’ll need you, kid.”

The partner had explained the firm’s assignment rationale no further and Roger hadn’t pressed the issue, he not knowing if some M&A partner had specifically chosen him, or his name had been pulled from a hat. He had accepted the offer because it was the only one from Chicago he had received (he’d gotten two out of DC and another from Kansas City), and Chicago was where he had to go. He had promised his mom that after he was done with law school, he’d return home. But that was before he met Joyce, and before he had actually lived in Washington DC, which he frankly liked a lot more than Chicago. As did Joyce as well.

Roger’s studies at Georgetown and his bar prep had not covered M&A in any deep detail. His understanding of the practice was basic: businesses looking to buy other businesses, or businesses looking to be bought by other businesses, or businesses looking to merge as a partner with other businesses; any of which required a law firm to facilitate the contractual processes.

It was this lack of knowledge, and a desire not to appear completely M&A stupid when he started work in the fall, that compelled Roger to go to the Lincoln Park library branch (where he signed up for a new card) in search of books to enlighten him on the details of M&A. And though he had not forgotten Joyce’s reminder the day before of his promise to keep August just for themselves, he didn’t see how some reading here and there was reneging on that.

Joyce, as it’s been seen, thought otherwise. He quickly tried to ease the situation by saying he only intended to do some light studying. “I’m not going to be pulling any all-nighters.”

“Oh yeah?” she said. “And what about all-afternoon-ers, or all-evening-ers?”

With a right hand raised as if he were swearing an oath before taking the witness stand, Roger promised he just wanted to get a jump on his duties for the coming autumn. He then stepped over to Joyce and gently took her in his arms. She offered no resistance as he kissed her lightly on her forehead, then touched his forehead gently to hers, holding it there, and softly saying, “I’m doing this for us, baby.”

She nodded once, and said just as soft, “I know, I know.” She feeling guilty now, although she did not know exactly why. With their heads still touching and their shadows cast against the kitchen wall in that abundant evening sunlight, Joyce said she he just wanted them to make the most of this little time they had before things got hectic after Labor Day, which was in reference to not only Roger’s coming job, but her own, she having secured a position at The Chicago Record newspaper where, on the same day Roger was to start with the law firm, she would begin a Downtown job as a clerk, digitally filing articles and photographs.

Roger kissed her on the mouth, and Joyce didn’t resist that either, the lip-locking tongue tag having its usual effect on her. And when Roger suggested softly that she turn the stove off, put what she was cooking in the oven to keep it warm, so they could have a, “lie-down,” (his phrase for daytime lovemaking), Joyce said okay.

In the bedroom, as they undressed, she thought that this was probably another case of her conceding. But at least this time she had good reason, for what was a better example of, “having time to just ourselves” than a spur-of-the-moment session with your man?

Later that evening, when, as the saying goes, “the barking and the biting were through,” Joyce lay with her head sideways on Roger’s damp chest, a leg thrown over his, the air immediately around them strong with the scent of their loving; Joyce thinking that it was moments like this that poets and singers were referring to when they spoke or sang of being happy, and that right now she was happier than she’d ever been with Roger or any other man; Roger now saying, while he lightly stroked fingers on her upper back, that they ought to forget about fixing the meal she’d started and put in the oven, that they should just order a pizza. Which made her happy too.

Over the next few weeks, Joyce and Roger enjoyed, what in later years they would sadly come to realize, was the most carefree period of their marriage. They slept in most every morning, went to the movies on uncrowded weekday afternoons, or to the crowded lakeshore where they sat on a blanket and under the shade of a beach umbrella. Once, they decided to see the lake from the eastern side and took a rental-car day trip to St. Joseph, Michigan, where they picnicked near Silver Beach. During that August, Joyce and Roger were able to do the kind of sightseeing many working Chicagoans seldom have time for—the amazing, four-state view from the sky deck of the Sears Tower; visiting the lions, tigers, bears, and more at the Lincoln Park Zoo; gazing up at the dinosaur skeletons at the Museum of Natural History; climbing into the snug confines of the captured-at-sea, World War II German submarine at the Science and Industry museum; taking a leisurely architectural boat tour on the Downtown branches of the Chicago River.

And also, time to not leave the apartment at all. Roger reading up on Merges and Acquisitions, he surprised at the sheer amount of documentation review that had to be done when a business retained a law firm to investigate a business targeted for purchase; so that the buying business would know exactly what it was buying before the sale: a document-by-document assessment of every piece of written information regarding the targeted company—minutes of board of trustee meetings, articles of incorporation, tax returns, any and all contracts and financial statements, and on and on and on; and that was just the due diligence part of it.

On more than a couple of occasions, over a meal usually, Roger waxed on to Joyce about some new aspect of M&A that he had read about earlier that day, she listening politely because listening politely when your husband was gassing about something you didn’t care about, was in her opinion, a wife’s duty. Her not caring wasn’t because she lacked the mental capacity to understand what he was talking about; she just had no interest in it. Like when Roger tried to explain the West Coast Offense used by professional football teams.

That month, in addition to the easy-peasy afternoon lovemaking, she and Roger’s engaged in thumbing through magazines devoted to houses from by-gone eras, with details like crown molding and inlaid wooden floors, clawfoot tubs and butler’s pantries. They agreed that when they eventually bought a house, it would feature the sorts of Craftsmen aesthetics they longed to live amidst. As to when that would actually happen, that they did not know. Given the current prices for such houses in what they considered “suitable” neighborhoods, the time would probably not be soon, what with Roger’s student loans still to pay, taking on the mortgage on such a house would not be prudent. Still, they could dream, couldn’t they?

PART 2: Working for the Man Every Night and Day

The law firm that hired Roger was named Weirdun & Bloom, the business occupying three upper floors of one of those Downtown skyscrapers where the building’s outer shell is all steel and glass. The firm’s offices, hallways, and meeting rooms were carpeted in dark grey, the walls of those spaces covered in large sections of mahogany stained wood, while the ceilings were equipped with fluorescent fixtures that had trellis-like screens fastened just below, greatly defusing the light and creating an overall effect that was shadowy and somber.

Lawyers from rival Chicago firms sneeringly called Weirdun & Bloom, “Weird Ones of Doom,” for its well-deserved reputation as being a tough place to work. Junior associates were expected to rack up 2,000 billable hours a year and most of the shop’s higher-ups had no time for touchy-feely stuff like saying thank-you. These traits were no doubt a by-product of the often times cutthroat atmosphere of the equity partners. Another common wisecrack among the firm rivals was: “At Weird Ones of Doom, you eat what you kill—and that includes each other.”

Though Roger had been a summer associate there, the relatively light responsibilities of an intern had not revealed to him the true nature (some would say depths) of the firm in all its glory.

This deficiency in his understanding was cleared up on his first official day on the job as a lawyer-in-waiting (those bar exam results still pending), he wearing a dressed-to-impress, dark gray suit with cuffed trousers.

After taking part in the usual first day activities with the 20-some other newbie associates: a meet and greet with equity partners, a tour of the firm’s shared facilities, etc., Roger was shown his office, a narrow room with a floor-to-ceiling window at one end. He was then directed up a set of internal stairs to an early afternoon meeting with a senior associate named Gary Sheets.

The guy looked to be around Roger’s age, his sandy-shaded hair parted on the left side with a sweep of locks over the upper forehead of his narrow face, his skin looking to Roger like it was displaying the last vestiges of a suntan.

Collar open, tie loosened, white sleeves rolled up to nearly his elbows, the tall Sheets leaned back in his chair, his right ankle resting on his left knee, a slender-fingered hand raised upright and holding a ball point pen that he clicked from time to time. As soon as Roger was settled in a wheelless chair the other side of the desk, Sheets got straight to the heart of things.

“You can expect to routinely be pulling ninety, to one-hundred-hour work weeks. You’re on call to this firm twenty-four seven. Later today you’ll be given a cell phone and laptop. Keep the phone with you at all times. As in, you don’t take a piss or dump without the phone within reach.

“As for the laptop, that’s for work only. No sports networks or porn sites, whatever. Got it?”

Roger said he did.

Sheets continued. “I see you’re married. If I were you, I’d sit down with the wife and explain things to her. Mainly, that there’s no such thing as work-life balance around here.

“She should forget about making plans for the two of you to go to plays or concerts or anything that requires making reservations, because from here on, your schedule is not your own.

“You have any children, Roger?”

Roger said no.

“Both parents alive and healthy?”

Roger said they were.

“Well, that’ll make things a little easier,” Sheets said, “less family-related stuff. Of course, if it’s a funeral or somebody in the immediate family is rushed to the hospital, that’s legitimate reason to be off work. But stuff like family birthday parties, family barbecues, graduations. Those are not reasons for you not to be on the job, or available to lend a hand if needed.

“Right now, we got a couple of deals close to closing, so everyone in our patch is pretty busy. For the next couple of weeks things may be a tad slow for you. After that though, things will definitely heat up.

“Now, if your wife is like most, she won’t like hearing what I’ve laid out about work hours and being on call, but the sooner she understands the reality of your situation, the better. That includes understanding that this’ll be the drill for the foreseeable future. And by that I don’t just mean for the next year, but for the year after that, and the year after that, and the year after that.

“When I started here, I worked one-hundred-and-twelve days in a row. I’m not saying that to brag, or to say you’ll have to do exactly the same. I’m saying it so you’ll understand that neither I or anyone I report to will have any sympathy for somebody bitching about all-nighters or working over the weekends.

“You and the two new arrivals to our practice area will start off helping with due diligence, which is boring as Hell I know; but understand that the equity partners, who are the reasons we all have jobs here, base a lot of their counsel to clients on what juniors send up to them. I’ve seen deals fall apart from some due diligence oversight.

“Our reputation is based on the perception outside the firm that we don’t fuck things up. From the bottom to the top, we don’t fuck things up. That’s why people hire us. That’s why you’re making a six-figure salary right out the gate. As a junior, we’re depending on you. You have anything to say?”

A bit flustered, Roger said, without thinking: “All that about the hours and not making plans, is that what you told your wife?” Roger immediately thinking: “Oh shit. Why did I say that?”

But Sheets did not look the least perturbed. “I made sure I told my second wife. The reason I have a second wife is that I didn’t explain those things to my first.”

Relieved that Sheets wasn’t angry, Roger thought this was a good point to mention all the reading he had done on mergers and acquisitions. But Sheets cut him off.

“You’re a first year, nobody here expects you to know anything. If I were you, I wouldn’t go spreading it around about that reading. Makes you look like a kiss-ass eager beaver. Same goes for that suit of yours.”

“What’s wrong with it?”

“It’s a little dressy. Dress casual is fine for associates. But hey, if you want to spend good money to get gussied-up every day like you were the President of the United States or arguing a case before the Supreme Court, go ahead. Any other questions?”

“Will I be reporting directly to you?”

“Not right away. To start you’ll report to the guy who reports to me. Name’s Alphie, you’ll meet him later.”

Roger nodded.

“Okay, then,” Sheets said. “I have to hustle you out. I’ve given this spiel to three people already today and I have three more spiels scheduled before I’m done. Course I clean up the language when speaking to lady newcomers.”

“Of course,” said Roger.

That evening at home, Roger sat Joyce down on the living room couch, so they were facing each other at a slight angle, their knees nearly touching, he holding her hands gently in his, her face growing increasingly distressed as he told her what Sheets had said.

When Roger was done, Joyce looked as if she were about to cry. “So, what you’re saying,” she said, “is that we won’t have a life. We’ll hardly see each other?”

“I don’t think Sheets really meant I’ll be working way late every weeknight and on every weekend. He was just preparing me—us—for the fact that there’ll be a lot of times when my work life will be like that.

“We’re going to be alright, baby,” Roger said, “You’ll see. Your husband is making a hundred and twenty-thousand dollars a year. With my salary and your salary, we can pay off my loans and be able to save up to buy our own home, just like we planned.”

Her hands still in his, she lowered her head and said softly, “I know, I know.”

For a fortnight, as Sheets had predicted, Roger didn’t have much to do, simple tasks like making sure items on a document checklist had been delivered. He not having to leave his office (a framed photo of Joyce on his desk) because the firm had recently jumped onto the digital bandwagon, its due diligence documents in a virtual data room instead of an off-site location full of paper files.

During this time, Roger usually got home around seven-thirty, he and Joyce having supper together, with him afterwards washing the dishes, pots, and pans.

Roger also had plenty of down time at work to chat with his two M&A, first-year cohorts, both of whom who were in their twenties. One was a pudgy Black guy, shorter than Roger, named Calvin Johnson, who three minutes into their first conversation let Roger know that his cousin, also named Johnson, had played for the Bears and was now an assistant coach with the Minnesota Vikings. The other was a curvaceous, dark-haired woman named Eva Flores, who said with a toothsome smile in her first conversation with Roger: “Not Mexican, not Puerto Rican—Nicaraguan.”

Eva’s office was next door to Roger’s office on one side and Calvin’s next door on the other, the trio more or less in the middle of a hallway of same-sized rooms that were occupied by second and third-year lawyers.

The “three newbies” as they quickly took to calling themselves, got to know the aforementioned Alphie, a mid-level who acted as if he were preparing for a future role as equity partner by not smiling much. He was one of those guys that, even if you saw him first thing in the morning coming off the elevator, always appeared as if he’d been in his clothes for the last twenty-four hours. His white dress shirts never seemed to stay fully tucked in his trousers, he was forever having to tug the slacks up, and the bottom points of his ties never quite reached his belt buckle. His brown hair was a bit tousled and the lenses of his thin-frame glasses were always smudged. Among themselves, the three joked about Alphie’s appearance.

They also got to know Bett, a petite woman with hair parted down the middle who had been a paralegal at the firm since forever. She had a somewhat nasally voice that was pure Old School Chicago and called everybody, “Hon.” Her area was directly across from the newbies, a wide, windowless, open space where the secretaries sat in cubicles.

It was Alphie who ended the two-week honeymoon period by directing them via email to a digital, due diligence index where each of them was to review certain contracts of a business that was the target of an acquirer. Memos from their review of the contracts were to be emailed to him within the hour. That was it. There was nothing about what they were supposed to be looking for or how brief or detailed their memos back to him should be.

Having never done M&A as a summer associate, Roger had no idea what to do. The only reason he could think of as to why Alphie had supplied no guidance was that Alphie obviously felt that reviewing contracts was so basic a skill, like writing a letter to Santa Claus or tying your shoe, that any first-year would know how to do it. And it was here that Roger also realized in a panic that none of the reading he’d done on M&A would be of help to him now. That reading had dealt with the process as seen from the rarified air of an equity partner. While due diligence and its importance was often mentioned, how one actuality went about doing due diligence was not.

In his email back to Alphie acknowledging that he had received and read Alphie’s marching orders, Roger included no questions. He hated asking others for help, especially from supervisors and teachers. Doing so, he thought, made you look weak in the eyes of whomever it was you asked. And even if that person was willing to help, they would never forget that you had needed their assistance; which would always reduce to some degree, the regard in which they held you.

At this point Roger got so anxious he decided to take a walk around the firm’s floor in the hopes that doing so would, through the miraculous power of movement, give him an idea as to what to do.

As he passed Calvin’s open doorway, Roger saw him switching his gaze from computer screen to a legal pad where he was leisurely jotting down notes.

Bett gave Roger a smile and wave as he passed her station. He nodded back. It was ten minutes later when he returned to his stretch of hallway and passing Eva’s open office this time, saw her leaning back in her chair with legs crossed at the knee, a slipper shoe dangling from the higher foot, her legal pad in her lap, and writing in what also appeared to be a leisurely pace.

The walk-around had produced no solutions for Roger. In his office, he looked at the small numberless clock on the desk next to the photo of a smiling Joyce; that smile no comfort to him now. He had a little over thirty minutes to go. What was he going to do?

A light knock startled him. He turned to see Bett in the doorway holding a manila folder.

“Got a second?” she said.

Roger said sure.

Closing the door softly behind her, she stepped over to him and spoke in a low voice, like she didn’t want Eva or Calvin to hear.

“Listen, Hon, I noticed your expression when you passed me. You looked a little dazed.”

Before Roger could offer an explanation, she placed the folder, which had a good stack of papers inside it, on his desk. She then asked what Alphie had sent him to review.

He told her.

“May I?” she said, pointing at the computer mouse. He nodded yes.

Bett leaned forward slightly and took control of the mouse with one hand while using the other to scroll through the documents; as she looked at the screen, her brown eyes narrowed, causing the wrinkles at the corners to spread out like sections of a hand-held fan. When she was done, she straightened herself and gave him a summary of what Alphie was probably looking for.

Lightly patting the folder, Bett said it contained copies of due diligence memos from deals gone by. Some from businesses that no longer even existed.

“You should find some things in here that’ll give you an idea how to memo Alphie.”

“I feel so dumb,” Roger said.

“Don’t,” said Bett. “The partners and upper associates always do this. Drop a bunch of stuff on a first-year and say, ‘You’re on your own kid. Sink or swim.’

“It was done to them when they started, and since they can’t get even with the people who did it to them, they do it to the people they can do it to. It’s stupid.

“Every fall,” she said pointing to the folder, “I’ve had to do what I’m doing with you for at least a few newcomers, and that includes some current upper associates who shall remain nameless.

“Now, understand, Roger, I can’t bail you out every day. Ask some of the second years around here if you need assistance. Some won’t be helpful, but some will. That Eva is a source too. You know she did her summer associate last year with an M and A practice group in New York.

“I could kiss you,” said Roger.

“That’s very sweet young man,” she said with a grin, “but I’m married and happily so. You better get cracking.”

“Even with these examples, I don’t think I’ll finish in time.”

“Then email Alphie that you’ll be late.”

“He’s not going to like that,” said Roger.

“True, but he’ll be way more irritated if he doesn’t know it’s coming late. Rule of thumb. If you’re going to get something in late to Alphie, Gary, a partner—anybody, always let them know just as soon as you realize you’re going to be late. Good luck.”

And with that she gave his shoulder a light squeeze patted and left.

Roger read through everything in the folder, got his memos written and sent, albeit quite late. He received no reply from Alphie.

That night a little after midnight, with Joyce sound asleep next to him, Roger’s phone pinged. It was a text from Alphie advising him of the several things he’d gotten wrong and that he, Alphie, had spent a good hunk of time correcting, which he would go over with Roger first thing in the morning: “My office, seven o’clock.”

Roger was there at seven and went straight to Alphie’s office, which had lots of memorabilia from Northwestern University where Alphie had done his undergrad and law school. Roger took furious notes as Alphie enlightened him on all of his mistakes. Roger offering no explanations because he suspected Alphie was not interested in hearing any.

Back in his own office, Roger had no time to digest any of Alphie’s points because by that time, there was another email from Alphie with the day’s marching orders that were more extensive than what he had sent the day before.

And over the coming weeks, that was how it went, every work day, which included a number of Saturdays and Sundays. Roger confronted by yet another task with little or no guidance, so scrambling around asking second and third years what to do, but they were able to give him only so much advice because they were up to their eyeballs in work too.

Roger had, of course, done contract study at Georgetown, but reading contracts for a class was one thing, having to plow through seemingly endless amounts of contracts and other dull-as-dirt documents was mind-numbing.

There were Change of Control Agreements:

A “change in the ownership of the “Company” which shall occur on the date that any one (1) Person, or more than (1) Person acting as a group becomes the Beneficial Owner of stock in the Corporation that together with …

And Certificates of Incorporation:

Any contract or other transaction between this corporation and one or more other directors, or between this corporation and any corporation, firm, association or other entity of which one or more of this corporation’s …

And By-Laws:

Every director, officer, employee of the Corporation shall be indemnified by the Corporation against expenses and liabilities including counsel fees reasonably incurred by or imposed upon him or her in connection with any…

Digital page, after digital page, after freaking digital page. And now, he usually didn’t get home until after nine o’clock, Joyce sitting with him, neither saying much as he ate from the plate of supper she’d prepared. Tired as he was, Roger’s ability to sleep at night was impaired by worry that Alphie might contact him, and that he, in deep sleep, would miss the message.

Every morning Roger awoke in dread of the day to come, which always wound up being like the days before, to be confronted by some aspect of law he had never heard of.

With Gary Sheets’ words very much in his thoughts, Roger felt he had no margin for error in anything he did, that some mistake on his part might derail a deal, get people fired. Alphie, every day or night with some curt email, pointed out something else Roger had missed:

An addendum to a document with no evidence of the contract that it was addended to made the contract null and void, no matter if a company had been billing and getting paid off that contract.

That it was always a good idea when reviewing contracts to make sure the contracts had been signed.

If a target business had most of its business coming from contractual agreements with only two other businesses, and those contracts were soon due to end—in six months, a year—the acquirer needed to know that. Because if the target business’s two main sources, when the contracts ended, took their business elsewhere, the target would be worth a lot less money, maybe not much money at all.

And as if all this weren’t bad enough for Roger, there was the fear that he might not pass the bar, the humiliation he’d feel when he saw the disdain in Alphie and Gary’s eyes, the pity he would see in the eyes of Calvin and Eva and Bett.

And in October, when at long last Roger learned that he had, in fact, passed the bar, he felt no joy. He hurried to the men’s room to sit inside a stall and weep in painful relief. Getting home so late that Joyce was asleep, he saw the two empty champagne glasses on the kitchen counter.

The weeks dragged on. The long hours forced Roger to miss all sorts of family and social events. And even when he wasn’t Downtown, he was always just a phone call away from Alphie or Gary beckoning him. More than a few times he left Joyce at a movie or restaurant to head to the office to address some out-of-the-blue request from a client, Joyce coming to dread the ringing or vibrating of Roger’s phone. Roger, of course, dreading the ringing and vibrating too.

Roger missed Thanksgiving, Christmas Day and New Year’s Eve.

A most disappointed Joyce made a point of keeping her feelings to herself. Not wanting to add to Roger’s obvious anxiety, she listened patiently when he complained of work, which he did on a daily basis, he voicing to her that he wasn’t sure if he could do this job. She did not tell him of her own work woes, how sitting in a windowless room at The Chicago Record newspaper and digitally filing photos, was mostly a drag; she felt her own office troubles were no comparison to those of her husband.

Joyce also told herself that few folks would have any pity for Roger and her, what with all the money they were together making. Even after paying down the school loan, for the first time in their adult lives she and Roger did not have to worry about making a bill. But what good was having ready money if you and your husband had so little time for any together fun?

Which is not to say they didn’t spend. Free at last from tight monthly budgeting, she and Roger indulged in more than a little retail therapy—a much larger TV and a vast cable package, new home computers for both of them, a new couch, a new bed, new cookware; impulse purchases of shoes and jackets and coats.

However, these purchases offered only temporary relief in the face of Roger’s workload. By mid-winter he quit complaining to Joyce about work because complaining wasn’t going to change anything. They resigned themselves to taking advantage of the rare weekday evening when Roger managed to get free. The rare weekend day when he didn’t have to go Downtown, they grabbed whatever spur-of-the-moment enjoyment they could, which included making love, which had really suffered under their stress, with them sometimes going weeks without intimacies.

By early spring, with the tsunami of work continuing unabated, Roger felt he and Joyce needed to do something to get off the treadmill they were on, tangible proof they were making progress in their lives. They needed to buy a house. Their dream house. Money be damned.

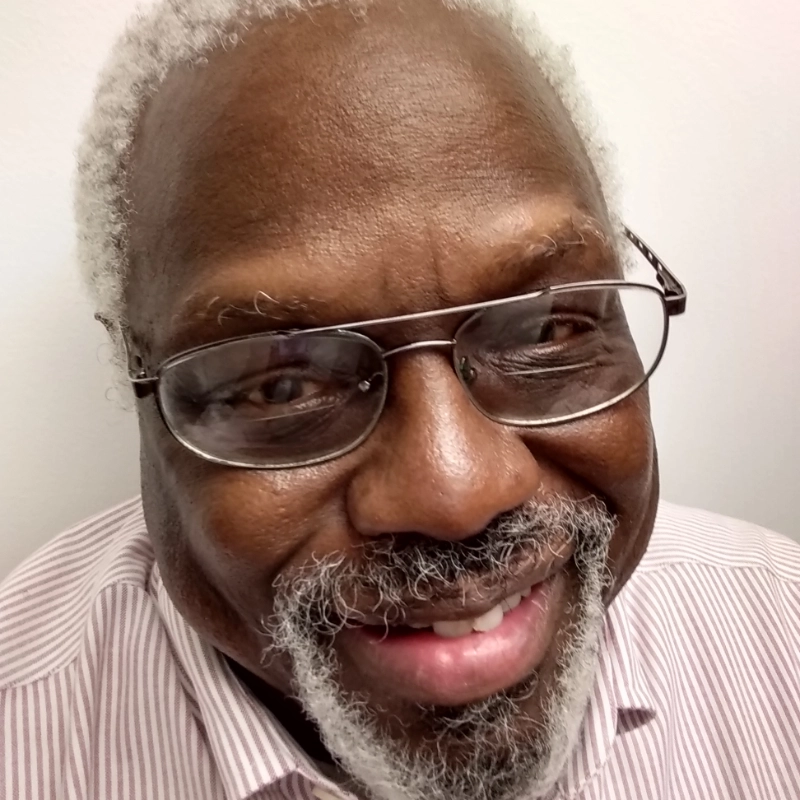

Eric Charles May is the author of the novel Bedrock Faith, which was the 2021 One Book, One Chicago selection by the Chicago Public Library, and a 2014 Notable African American Title by Publisher’s Weekly. A Chicago native, May is a former reporter for The Washington Post, and a Professor Emeritus at Columbia College Chicago where he taught in the Creative Writing Program for 41 years. A past recipient of the Chicago Public Library Foundation’s 21st Century Award, he is a past President of the Guild Literary Complex, a member of 2nd Story, and a selection committee member for the Harold Washington Literary Award. His fiction has also appeared in the magazines Fish Stories, F, Hypertext, Solstice, and We Speak Chicagoese. In addition to his Post reporting, his nonfiction has appeared in Sport Literate, the Chicago Tribune, and the personal essay anthology Briefly Knocked Unconscious by a Low-Flying Duck.