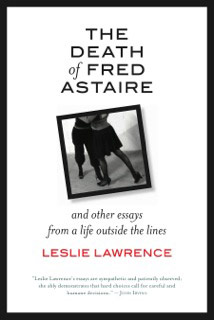

“When I was a child I accepted without question that I would one day be a mother.” So begins the opening essay “The Death of Fred Astaire” in Leslie Lawrence’s collection. But this will be no traditional motherhood, for Leslie has found the love of her life, “Sandy—a sturdy, vital, grown-up woman with a full-throated laugh.”

“When I was a child I accepted without question that I would one day be a mother.” So begins the opening essay “The Death of Fred Astaire” in Leslie Lawrence’s collection. But this will be no traditional motherhood, for Leslie has found the love of her life, “Sandy—a sturdy, vital, grown-up woman with a full-throated laugh.”

Lawrence takes us back to her childhood, happy by all accounts, her expectations of a traditional marriage, and the evolution of her sexual identity as lesbian. With Sandy she begins to plan how to do this thing, “Having a baby without a man.” It’s a trying and tender four-year journey, “making it up as we go along?” In the summer before Lawrence conceives, Fred Astaire dies and the depth of her grief surprises her. “Not the soloist hoofing it with his cane, but Fred together with Ginger,” she realizes. It’s a new and different dance, and Lawrence with her partner is inventing the steps, as she reinvents her life.

“But I was a girl—a small cute Jewish one raised before the second wave of feminism,” she concludes in “Fits and Starts.” A modest assertion, yet she embraced those tenets and fleshed them out, and began to create of body of work that chronicled the seismic shifts in American culture and sexual politics from the latter half of the twentieth century to the present. Writer, feminist, teacher, dancer, lover, lesbian, mother, widow, and wise woman. Still rooted in her Jewish heritage—a Post Testament Devorah. Can one do better than be a prophetic witness and activist for one’s time?

In “My June Wedding,” a celebration of her and Sandy’s marriage at Cambridge City Hall with countless other same-sex partners and thousands of supporters, Lawrence utters a joyful rant of “I could never have imagined…” (why do I imagine her dancing with timbrel), “that the only man at my marriage would be my fourteen-year-old son in sneakers and a shirt in serious need of ironing.” ”Still, I could never have imagined that legal, state-sanctioned marriage between same-sex couples would be an option in my lifetime.” And on, she chants. “Well, why not?” I want to exclaim. “You were among the trailblazers who made this possible.” Few I know embody the qualities boldness and humility.

Lawrence writes with a mastery that can turn on a dime from lyric grace to down-home colloquialism. In “Karl Will Bring a Picnic,” a tribute to her uncle, “How could I not adore this man who gave me so many of my memories of song and speed and light?” is enjambed with this jumbled one-sentence paragraph: “Even if he sometimes gets carried away, as with this picnic, and especially this egg business.” It’s a pratfall, and I love it. A nonsense sentence that stands in for Karl’s eccentric, exuberant personality—the method of his gladness.

Even the short essays are chockfull, and expand in surprising ways: “Provincetown Breakfast,” yoghurt & berries topped with grape nuts, a side of Eros & Thanatos; “Enough Tupperware,” a meditation on illness, and greed, and letting go; and “Yard Sale,” Who could imagine how a “consuming romance with other people’s garbage” could be redeemed by Thomas Moore’s Care of the Soul?

“On the Mowing,” the essay that opens Part III, is the artistic and spiritual center of the collection. Lawrence has found a cabin at the top of a meadow in the woods of New Hampshire, a view of Mount Monadnock; a cabin of her own to write in. But it’s the meadow—“the mowing” as it is called—“the glory of so much tall grass doing what it does best—swaying in the bluesy spring wind,” that keeps her coming back.

She chronicles the history and geography of the place, her local friends, picking blueberries, Sam’s August birthdays, fireflies and comets, and gin and tonics, gaining a life partner in Sandy, and grieving her loss from cancer. Where all the lives that are her life find their way to the dance: composition and improvisation. Rooted in body and bending where she wills: an ancient dervish whirling in place, a modern Duncan given over to the wind’s wild grace. Mowing, she whispers like a prayer, over fifty ways. She offers her hand. Come—Join in the dance!

In “What Can You Do?” perhaps the darkest essay, she attempts to resolve the aftermath of Sandy’s death.

It seems to me, so far anyway, that death is simply this: the stark, colossal goneness of a once substantial, infinitely complex presence.

I get the feeling she wrestled this from an angel. It knocked the wind out of me.

The essay opens in Silver City, New Mexico in the December after Sandy’s death in October, and closes the following June, at night in the mowing, at her cabin in New Hampshire. Nearly nine months since her beloved’s death. Enough time for a rebirth of hope, perhaps in the courtship of the fireflies?

I tried to discern some sort of pattern or rhythm to the flare-ups, but soon, realizing it was hopeless, I just stood there transfixed. For the briefest of moments then, it came to me that here, at last, was Sandy speaking to me. But the next night when I stood there again and saw just as many flies, dancing just as jazzily, it came to me with the same certainty that they were just bugs calling to each other in the dark.

I didn’t expect the dark turn of the final sentence. I still worry it like a prayer bead. I want to say the second night’s experience does not negate the first night’s one. Her beloved’s presence and her absence could both be true.

Where to go when you’ve still fields to mow? To the Dance—“…this body of mine while it’s still my friend.” And to Beauty: The penultimate gathering of this collection: “Wonderlust: Excursions through an Aesthetic Education.”

“Wonderlust,” a virtuoso twenty-three movement prose-dance, gathers the variations on the theme of her personal manifesto: “I’ve always been greedy for more than my one little life—and so the drive to invent, recollect, and reinvent.” One senses her poise and determination. I can almost hear her whispering Che Guevara’s meditation “I have polished my will with the delight of an artist” as the curtain rises on Part IV.

She begins with “Dancing Outside the Lines,” a dance course that juggles “the artist’s desire for ownership, freedom, and control with the rewards that come from submission, limitation, and chance” and closes with “Like Life, Like Art,” a community theatre performance titled Landlines, developed by Anna Schuleit, at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire. Let me share some of the highlights of the “program” and leave the delight of the performance to you:

Learning to dance to Bach’s Goldberg Variations by Glen Gould; arrested by a red geranium; “art making” in the “Kate Ransohoff way”; painting in the Southwest with Georgia O’Keeffe as muse; questioning the scales of Elaine Scarry’s On Beauty and Being Just; experiencing the “oozing eros” of Roethke’s poetry; finding joy in her teenage journal; learning the “perform pieces” of Ken Maue; becoming a midwife for Sandy’s death; a deep breath of wonder with Sam at Oberlin, her alma mater.

“At the Donkey Hotel” is a brave choice to close the collection. Touring in Fez, Morocco, she visits the veterinary hospital, part of her routine itinerary whenever she travels. Daughter of a vet, as a teen she helped out in her father’s hospital. A farmer enters carrying a three-day-old foal close to death. She volunteers to help. The foal dies, but not without a valiant effort by Gigi, the vet, giving mouth-to-mouth when medicine fails.

When recounting the event to her traveling companions, one asks if the effort might have been staged to give comfort to the farmer that everything had been tried. The question shakes her, yet she opens herself to research the possibility. How recent has it been since we’ve mourned with Lawrence the last days of her beloved? A few minutes, pages? Why this closure?

She searches the Internet, sorts the data, weighs the evidence, and finds herself thinking about a story by Eudora Welty, “A Worn Path,” about a very old woman making an arduous monthly trek to a clinic to get medicine for her sick grandson, then “starts the journey home, and that’s it—the end.” Welty wrote an essay as a response to the many letters asking if the grandson is actually dead. “The only certain thing at all,” she said “is the worn path. The habit of love … remembers its way….The path is the thing that matters.”

Lawrence concludes where she began the journey of this work: “You could say that I (petite, fearful by nature, raised before feminism’s second wave) have worked all my life to be brave enough to find my way alone to a genuinely foreign land.…Then, when the day turned really interesting….I had a place within a small circle of rich and poor, dark and light. And when Gigi funneled her breath again and again into the donkey, we, all in the habit of love, breathed along with her.”

In the end it is Lawrence’s unflinching ability to welcome the darkness with the light, befriend the pain with the pleasure, as the Sufis advise, find beauty in the bone shop of the heart as well as Bach that makes this body of work, like her own loving, yearning, dancing body—Alive.

oops … Mis-spell of name… Ezzell Floranina!

lovely review… I look forward to holding it in my hands and reading, tasting the moments shared above and more…thanks, Leslie!